The journey of one Miami student to become a naturalized citizen in America

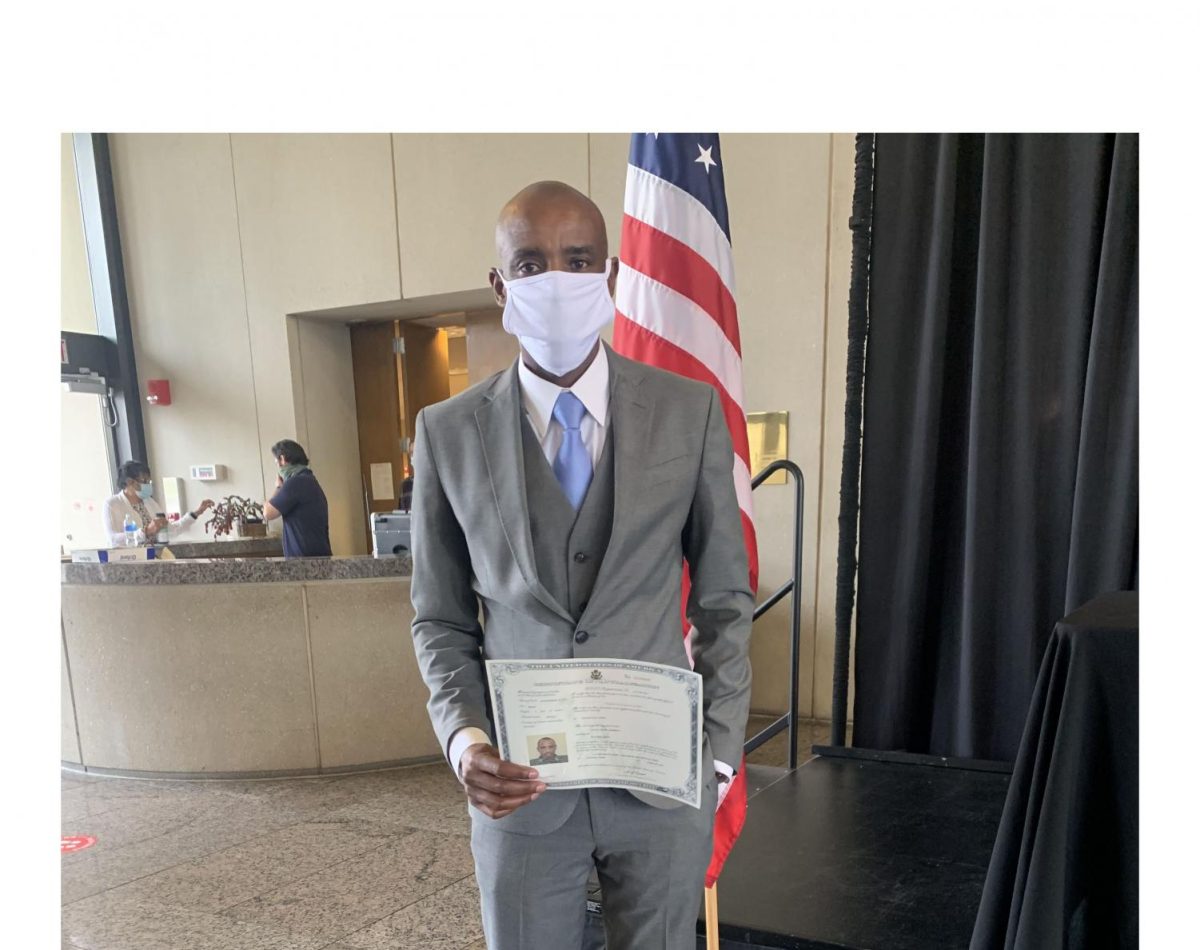

Photo provided by Godwin Agaba

Godwin Agaba holds his naturalization certificate the day he took his oath of citizenship on Feb. 8, at Sinclair Community College in Dayton.

April 16, 2021

For each immigrant seeking to become a naturalized citizen in the United States, there are unique challenges, but the sentiment for those who complete the process is always one of hope.

My hope was realized on April 8, when, together with 98 other people from 68 countries, I took my final step to gain American citizenship and recited the oath of allegiance to America.

We stood proudly as we recited the oath in the Sinclair Community College auditorium in Dayton, Ohio. As naturalized citizens, we beamed triumphant smiles as we waved our American flags and certificates high.

Some of us couldn’t hold back tears of joy. Though the event is celebratory, for many new Americans the path to citizenship has not always been easy. Mine was uniquely tortuous.

The journey to my American dream began in February 2010 when I fled Kigali, Rwanda for reasons related to my work as a journalist. Relying on unusual survival instincts, I made my way out of Kigali, Rwanda undetected and sneaked over the border into neighboring Uganda through secret, unauthorized routes.

Once on Ugandan soil, the next step was to find a way to the Western world as the Sub-Saharan region was not safe for me. There was no question of me staying in Uganda, even though I was a Ugandan; born in Uganda, with a Ugandan passport, but working in Rwanda. I couldn’t seek refuge in my own country. I had to temporarily relocate to Kenya to start the process.

Deciding to try to come to the United States

The relocation process was long and winding. It took two years and eight months, notwithstanding the fact that mine was an emergency case. It normally can take between five to 10 years.

In Kenya, I approached the United Nations offices to start the process. I was interviewed and my case was sent to Geneva for the decision.

In seven days, I was called to pick my U.N. protection mandate. The next step was to sit for a resettlement interview. After two weeks, I was called with the results of that interview. Over 20 countries had offered to settle me. First was the Netherlands and second was Canada. The USA was number 10 on the list.

However, I never wanted Europe. The only thing I admire in Europe is football (what Americans call soccer). I omitted all European countries and continued to ask for relocation to one of three other countries — Canada, the United States and Australia. I was given two days to submit my country choice. I eventually zeroed in on the United States.

I chose the United States because I wanted to live the American dream and I wanted an American education. With the United States being one of the most culturally diverse countries in the world, I thought I would adapt very fast and easily.

I submitted my choice and, after a few weeks received a phone call from Resettlement Support Center Africa (RSC Africa), inviting me for an interview. RSC Africa operates as a U.S. refugee resettlement program in Sub-Saharan Africa with the U.S. State Department Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration. It is responsible for the preparation of refugee case files for adjudication by Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), as well as the out-processing of all approved cases.

After the interview, my case was sent to Washington, D.C. After months of waiting, I received another phone call from RSC Africa. This was to invite me to face USCIS officers from Washington, D.C. for an interview on whether to accept or deny me entry to the United States.

I was interviewed by an old man whose name I do not recall. The quizzical look on his face caused my stomach to churn, but I was confident and what transpired during the interview will forever keep me grateful to him. His first question was: “What were you in Rwanda?” My answer was: “Just a news reporter.”

He brandished a scanned page copy of The New Times story entitled: “Rwanda Media Fraternity Disowns Godwin Agaba.” The New Times is a daily newspaper in Rwanda. He explained that the reason he was asking was because after I fled Rwanda, “all these officials and directors met to discuss you.” He immediately concluded that The New Times story confirmed my threat. He made my case “an emergency.”

After a week, I was called for a medical checkup in a Nairobi hospital. This process also takes months to complete and was handled by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which handles medical and travel arrangements of migrants.

On Dec. 10, 2012, I was called to IOM offices, located in Westlands, Nairobi, Kenya to sign for my travel loan and to receive updates on my travel arrangements. Refugees traveling to the United States are issued loans by the IOM to pay for the costs of their transportation from overseas to the U.S.

A promissory note is signed by every refugee 18 years and above prior to arrival in the United States to confirm the refugee’s agreement to make regular monthly payments. This is an interest free loan and the beneficiary begins to pay it back six months after arrival. The repaid funds are then used to transport other refugees. I did pay back my travel loan of $1,440.

My flight from Kenya to Cincinnati – connecting in London and Miami – was set for Dec. 15, 2012. Departure time was 8:30 p.m., East African Time. Reaching at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA) for checking out, I was told I would not travel. The reason? My clearance checks had expired. What was the problem?

Turned back at the departure to wait again

USCIS had treated my case as an emergency, which is why my clearance security was for only three months. But three months elapsed before the medical process was completed. So, I was told by airport officials to go back. This was at night. I had no money to take me back to Nairobi, Kenya, a distance of 14.7 miles. I had to contact some organizations – The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), The Doha Center for Media Freedom (DCM) and Article 19 officials, who arranged my stay in Nairobi, Kenya as I waited for my security clearance to be updated.

After more than six months of much anxiety, as Kenya is within the East African region, where I was a man on the run, I was called to IOM offices on May 24, 2013 for my travel updates. I was issued with a new air ticket reading departure time as 9:00 p.m. on June 3, 2013 (JKIA to Zurich – New York – Chicago – Dayton, Ohio). This was to be my first journey to the United States.

The journey was largely peaceful, save for a little discomfort due to air turbulence. On arrival in New York, we found that Chicago flights had been suspended due to strong wind. I was given a hotel for the night. I arrived in Dayton, Ohio the following day. Finally, after three years on the run, I was in America!

In Dayton, Ohio, I was welcomed by Catholic Social Service of the Miami Valley, a refugee resettlement agency. The state of Ohio welcomed me with shelter, a telephone, bus ticket and a little money. I was to find work in two months.

At the back of my mind was going back to school. But I had to first organize myself, get a car and settle in the community. After two years, I went to Miami University to seek admission. I was given a placement exam (English and math) and Miami contacted Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB) for my Ordinary level certificate. The policy here is that they don’t allow a student to submit foreign academic papers. The school contacts the examination board of the country directly.

During orientation for new students, one of the topics was balance – how to balance work and education. Being a college student is a priority, but bills have to be paid. The key to balancing school life and work is time management. I parted ways with partying or socializing for the last four years to be able to cope.

As a new person in the United States, I needed to learn a lot of things including the ways of the people. Miami is a diverse university community. I have learned a lot from Miami. I became friends with students, local and international, and the teaching staff. I have made social connections and integrated meticulously.

The America I now know

The U.S. immigration system can be extremely difficult to navigate and the application can take “forever.” One must successfully pass six stages to gain citizenship. An immigrant must first become a permanent resident (green card holder) and must live in the United States for five or more years, be of good character (checks here are very vigorous). One must be able to read and write, speak basic English, demonstrate an understanding of the principles and ideals of the U.S. Constitution, have a basic understanding of U.S. history and government and take the oath of allegiance to the United States.

With my case, there were a few things to sort out before I reached the stage of taking the oath. One had to do with support: I have two children, Samuella and Isaac, who live with their grandparents back in Uganda. Both children are listed on my naturalization application form. Question 30 in section H on form N-400 asked: “Have you ever failed to support your dependents or to pay alimony?” The goal of this question is to determine whether you are a person of good moral character, remembering that good moral character is a fundamental requirement for citizenship. Failure to pay child support is considered a failure of moral obligation by the USCIS, so I had to prove how I pay school fees; provide bank statements showing how I send money for upkeep, who receives it; school reports, and so on.

Second, was the issue of names; there was an error in the order of my names resulting from my previous interviews in Kenya. Correcting that mistake was not easy. They thought I was hiding or dodging something. They had to verify from different sources, which is another long exercise of waiting.

Then came 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic nearly brought everything to a halt. But eventually all hurdles were cleared and on April 8, I finally took the naturalization oath and recited the Pledge of Allegiance, as follows: “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the republic for which it stands, one nation, under god, indivisible with liberty and justice for all.”

Upon becoming a naturalized citizen, when I shared the news with Professor Joseph Sampson he shared it on the professors’ email chat group. I was overwhelmed by congratulatory messages from university professors, evidence of the love and brotherhood at Miami University and the community at large. This is the America I dreamed of, the America I know!

Godwin Agaba is a senior at Miami University, majoring in journalism and English creative writing. He is a reporter for the Oxford Observer this semester.