Miami suffers housing revenue and capacity losses due to COVID-19

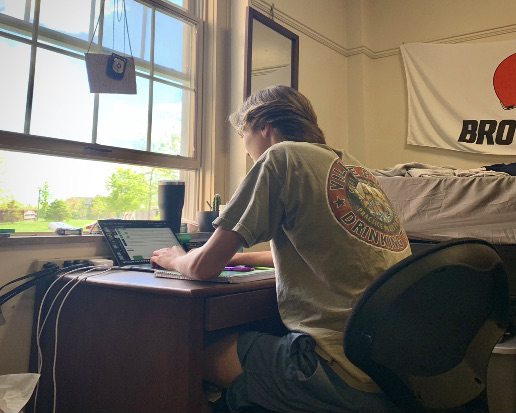

Aidan Blakley working at his desk in Havighurst Hall, located on Western Campus, before finals earlier this month.

May 27, 2021

Miami University is still grappling with the effects of COVID-19 over a year after sending students home and moving classes online.

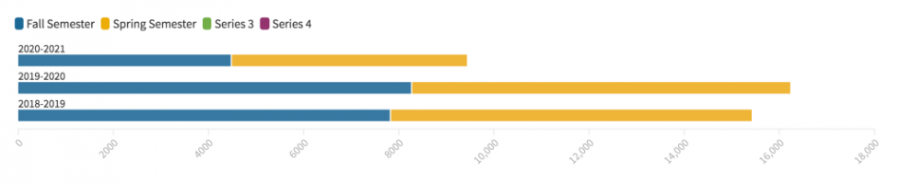

In the fall of 2020, Miami University dorm occupancy fell to 60% when students living on campus returned for the unprecedented semester.

Miami opened its 42 dorms to the 4,500 students who chose the on-campus housing option. This is a significant drop from the previous two years in which residence halls were filled with approximately 8,000 or more students.

“Typically in the spring, we would be closer to 95% or 96% so this is definitely a reduction,” said Brian Woodruff, the director of Housing and Operational Services at Miami. “It is very unusual. We usually have fewer students in the spring than in the fall,”

The spring 2021 occupancy was similar to the fall with only about 5,000 students paying for room and board. Miami gave students attendance options including living on campus or going remote.

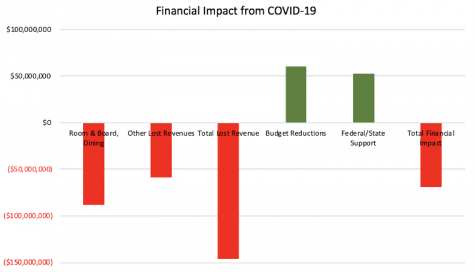

Because of the low number of students living in dorms, room, board, and dining losses totaled $87.7 million. Housing and dining are auxiliary operations that are merged under a general category that has a set of fees that students pay for the services being provided.

Reducing double and triple occupancy rooms was important to eliminate risks and Miami tried to offer more single-room options, Woodruff said.

First-year Aidan Blakely moved into Havighurst Hall last September and was one of the students placed in a triple with two roommates. He said dorm life has been exciting despite the many challenges due to COVID-19.

“I liked the idea of being in a dorm because it gave me a more normal college experience. I knew I would meet people through the hall,” Blakely said. “But, I did notice that COVID caused less occupancy in the dorms. On [my half of the] floor, there are only about 20 people and many had to quarantine throughout the year.”

Havighurst Hall is ranked number two on the list of dorms with the most students, housing 252 people. Hahne Hall was number one and Presidents Hall was number three, both with approximately 250 students.

The university’s total lost revenue was $146.6 million in 2020 due to the pandemic. However, offsetting grants, including state and federal relief funding, and budgeting reductions brought the net impact to $69.3 million.

Miami expected many of its budgeting issues. David Creamer, Miami’s senior vice president for finance and business services, and treasurer, said the university was looking for ways to manage the financial impact while keeping students safe.

“We were looking at things long term and how to respond to students’ needs reflects on the values of the university,” Creamer said. “We trusted students to execute what they indicated in their plan. If they certified in their plan that they would stay at home, then that qualified them for certain reductions.”

Creamer said the University had no way of enforcing students to stay out of Oxford if they did choose the off-campus option. Some students, including sophomores who wanted to return to campus earlier than the September move-in date, chose to live off-campus in apartments or houses in Oxford.

Lilya Smith, a sophomore last academic year, said she chose to get an apartment because she wanted to have her own space during COVID.

“When we were informed about opting out of living on campus, my friends and I began looking for off-campus housing,” Smith said. “This was a good decision for me because I had the opportunity to live in my own apartment with my own bathroom and kitchen instead of living in a dorm hall with a communal bathroom and no kitchen during COVID.”

Smith said a majority of the people she knows did choose this option because dorm-living during COVID would be difficult. Many first-years and sophomores had to weigh the options of the living choices.

Sophomores were able to opt-out of the two-year contract this year.

“The understanding is they were not to be on campus,” Woodruff said. “Ultimately the Miami card doesn’t work and they can’t do anything on campus. I have heard from some that sophomores are likely living off-campus.”

Smith said she noticed the change in her tuition cost from opting out of the dorms and received a $1,000 credit for being a remote student.

“It has definitely been a different experience and interesting transition from freshman year,” Smith said. “I’ve enjoyed living in an apartment and having my own space, but I am excited to be back on campus for in-person classes.”

State and federal assistance aided Miami’s financial impact by offering assistance that granted $52.7 million to the University. Money from the CARES act was given to assist students, specifically those who had applied for financial aid or received the Pell Grant.

“We are optimistic that things will be more normal,” Creamer said. “For the freshman and sophomores, it has been a completely different experience. Hopefully, we will be able to restore historically offered experiences next fall.”

Miami is scheduled to return to in-person classes and regular dormitory requirements for freshmen and sophomores for this year’s fall semester.