Pandemic impacts Miami’s out-of-state student enrollment

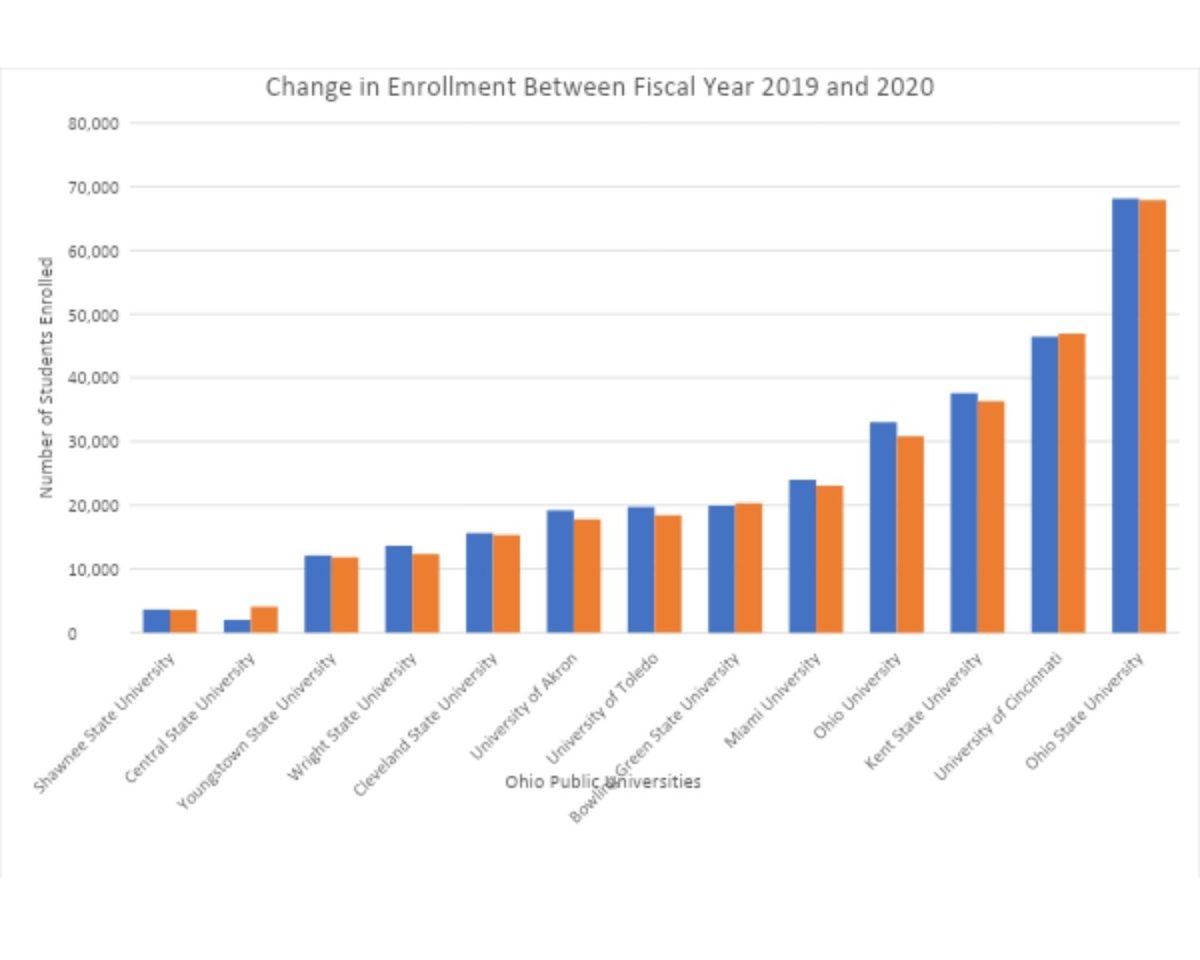

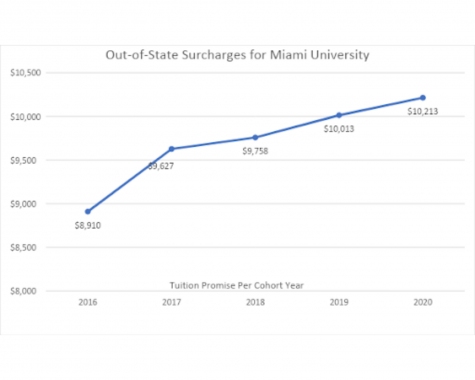

Chart created by Leanne Stahulak

Enrollments at most state universities in Ohio dipped from 2019 to 2020.

May 20, 2021

For the last decade, around 40% of Miami University’s student body has been non-Ohio residents. This includes both domestic and international students, some traveling from as far as China, or as close as Kentucky or Indiana.

But when the COVID-19 pandemic hit last spring, high school seniors across the U.S. watched their opportunity for a normal college experience crumble as campuses shut down and college towns emptied out. While universities scrambled to reconstruct their curriculums into hybrid and remote formats, these high school seniors reconsidered whether attending an expensive out-of-state school like Miami was worth it.

A number of them decided it was not. Across several four-year public universities in Ohio, enrollment numbers dropped last spring as students decided to stay closer to home, consider alternative forms of higher education or take a gap year. Wright State University experienced the most severe decline between the 2019 and 2020 school years as enrollment dropped by almost 10%, according to the Ohio Department of Higher Education.

But Bethany Perkins, Miami’s assistant vice president, and director of admissions, is more concerned with Miami’s yield rate, which is the number of enrolled students divided by the number of admitted students. Between 2019 and 2020, Miami’s yield rate dropped by 3%, which is the largest fluctuation the university has seen in a single year since 2008.

Perkins witnessed a 2% drop in yield rate for out-of-state students specifically, but for the upcoming 2021 fall semester, she’s already seen a huge rise in domestic non-resident applications. While the yield rate won’t be available until later this fall, Perkins said that the number of out-of-state applications shot up by 11% this spring.

While several factors contributed to students choosing to put off enrolling at Miami this past year, Perkins said those same factors are pulling students out of their homes and to colleges across the country.

“Did you enjoy the past year as much as you did the year prior?” Perkins asked. “Absolutely not. So, what we’re seeing, feeling, hearing from our students is that they want the full college experience. They’ve had a year of remote classes and they’re sick of it… They’re saying, ‘I’m ready to go far away to college because I’ve had plenty of time with my family this past year.’”

That’s the philosophy Jake Ruffer took last May when he decided to attend Miami for the fall 2020 semester. Ruffer is from Portland, Oregon, and even before the pandemic, he knew he didn’t want to attend a school in Oregon. While he was quarantined with his family for his last semester of high school, Ruffer had plenty of time to consider his college options.

By decision day, Ruffer was down to The Ohio State University and Miami. Because his parents were Miami Mergers, the university offered Ruffer a sense of familiarity and comfort, as well as an excellent journalism program and campus life. But cost also played an integral role in Ruffer’s decision to choose Miami over OSU.

“Once we got out of the realm of in-state tuition, everything was more expensive,” Ruffer said. “But Miami certainly offered more (financial) help than OSU.”

OSU and Miami have the two largest out-of-state surcharges compared to the other four-year public universities in Ohio. Both schools charged more than $10,000 for out-of-state fees this past school year, even though the average surcharge for Ohio public universities was $4,615. The University of Cincinnati, which had the third-highest surcharge, cost only three-quarters as much as Miami’s fee.

Senior Vice President for Finance and Business Services David Creamer said that when calculating tuition costs, the university starts with larger tuition rates and then estimates how much financial aid enrolled students will receive to offset the total cost.

“We don’t just need to know how many students are enrolling, but we need to know the precise composition of the scholarships that they have been offered to enroll,” Creamer said.

Tuition costs rise about 2% each year in concurrence with inflation changes, Creamer said. But with Miami’s Tuition Promise, families are guaranteed to pay that one rate for all four years their child attends the school.

Out-of-state surcharges are also influenced by mandates from the Ohio General Assembly, which contributes to the university budget and can make decisions about in-state tuition costs. If the legislature doesn’t want in-state tuition costs to rise, Creamer said, then Miami has to increase the out-of-state fees that much more to make up for inflation changes. The university must follow these mandates even if the general assembly doesn’t contribute as much as it has in the past.

“The share the state pays of our budget has unfortunately kept going down over the years,” Creamer said. “And so today, about 9% of everything that the university receives (comes from the state), so it doesn’t have the impact it did probably 40 years ago when it was about 30%.”

Miami makes up for its rising out-of-state tuition costs by offering competitive scholarships, like the one it awarded to Ruffer. Perkins said the university also has to be competitive because declining birth rates in the 2000s and the 2008 housing crisis have led to fewer high school graduates and prospective college students.

“Because Miami has historically seen a lot of students coming from New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Connecticut, that steep decline [in the number of high school graduates] that impacted the regional institutions there has also impacted Miami in a big way because those are big feeder areas for us,” Perkins said.

But with a 10% increase for all first-year applications for the upcoming 2021 school year, Perkins said she isn’t concerned that Miami will lose many out-of-state students. She’s confident that the university’s gorgeous campus, top-notch programs, and bustling campus life will draw many to Oxford in the years to come.