Miami Stanton-Bonham House honors Miami’s past with feminism, Myaamia tribe

May 13, 2022

The Stanton-Bonham House at the corner of Spring and Oak Streets is a landmark structure that has provided homes for Miami University president, pioneering thoughts on the rights of women, and the study of the Myaamia tribe, language and culture.

The Italianate-style brick house was built in 1868 by Robert Stanton, who served as president of Miami from 1866 to 1877. Stanton was the brother-in-law of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a famed women’s suffragist and lecturer, and contemporary of such women’s rights luminaries as Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott.

Cady Stanton stayed in the house in 1870, while traveling on a national lecture to an Oxford/Miami audience in the chapel of Miami’s Old Main, now the site of Harrison Hall.

“Our Girls” was a speech she gave throughout her career, which criticized male-dominated society and urged reforms in the areas of voting, property ownership, fashion and more.

“The coming girl is to be healthy, wealthy, and wise. She is to hold an equal place with her brother in the world of work, in the colleges, in the state, the church and the home. Her sphere is to be no longer bounded by the prejudices of a dead past, but by her capacity to go wherever she can stand. The coming girl is to be an independent, self-supporting being, not as to-day a helpless victim of fashion, superstition, and absurd conventionalisms.”

–Excerpt from Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s “Our Girls.”

After Robert Stanton resigned, the house was sold to Robert McFarland, a professor at the university. McFarland later became Miami president and his daughter, Lizzie, was among the first women to attend Miami. She lived with her father in the former Stanton house. Later, his other daughter, Frances, and her husband, Llewellyn Bonham, inherited the house upon McFarland’s death in 1910 and sold it to Miami University in 1940 in exchange for an annuity that allowed them to live there.

When a fire damaged the home in 1942, the Bonhams moved out and since then, the university has changed its use multiple times. It was the speech and hearing clinic, office of public safety and the graduate school office. It was also an Honorary Consulate of the Republic of Poland because the Dean of the School of Engineering was an Honorary Consul and had office space in the building.

It is now the university’s Myaamia Center, which works to preserve the culture of the Myaamia Tribe of Oklahoma.

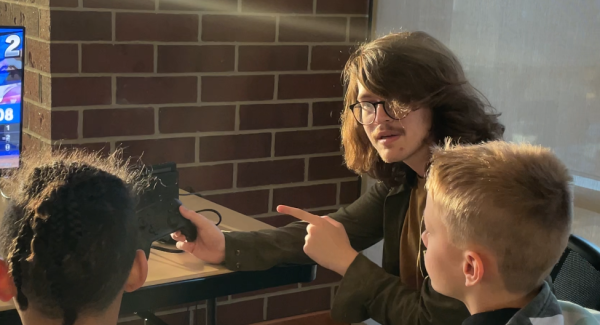

As the current Myaamia Center, the structure plays an important role in helping Myaamia tribe youth get a college education.

“The first Myaamia Students came to campus in 1991 and there were three of them. There were two undergraduates and one graduate student, and from those first three in 1991, we’ve now grown to 38 now,” said Andrew Sawyer, the education outreach specialist at the Myaamia Center. “So, it’s been slowly growing over time and with each year we are hitting a new mark with the number of Myaamia students that are coming to campus.”

The relationship between Miami University and the Myaamia tribe started when its chief, Forest Olds, visited Miami University while on a business trip to Cincinnati. Members of the university’s administration gave him a tour of the campus, and he was later invited back to help the president in an unveiling of a painting of a kneeling Miami Indian.

Olds’ successor, Floyd Leonard, continued to visit the university and oversaw the creation of the Myaamia Center. Today, the center prides itself on its attempts to help tribal students receive an education and raise awareness of their culture.