‘Wicked’ author reflects on his love of reading in Lecture Series talk

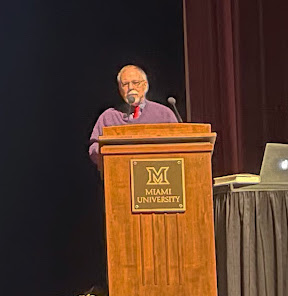

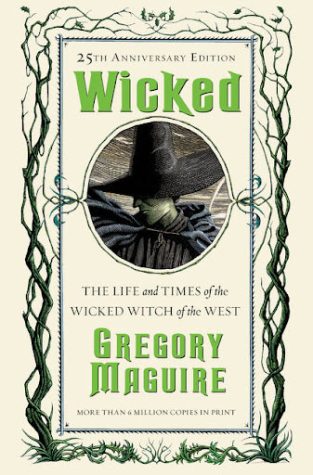

Gregory Maguire, best-selling author of the 1995 novel “Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West,” spoke at Miami’s Hall Auditorium Monday night.

February 18, 2022

Gregory Maguire, the best-selling author of the 1995 novel “Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West,” spoke at Miami University’s Hall Auditorium Monday night on the significance of literature and creativity.

Speaking as part of Miami’s Lecture Series, Maguire traced his love for literature to his early childhood, when his siblings bonded over a shared passion for reading and strict rules against excessive television. Reflecting on his lower-class upbringing, Maguire emphasized the importance of seeing himself and his hardships in the heroes of his favorite books.

“Once I got to be a surviving grown-up, I realized that my access to great children’s literature was part of what allowed me to survive some difficult circumstances,” Maguire said.

During his lecture, Maguire stressed a crucial exception to his parents’ limited allowance of television: an annual viewing of Victor Fleming’s 1939 film “The Wizard of Oz,” whose central antagonist left a distinct impression on him.

“(The Wicked Witch of the West) was so evil,” Maguire remembered, “so wicked that it was even part of her name. ‘Wicked Witch.’ It’s a capital ‘W’ in (L. Frank Baum’s) book!”

Baum’s 1900 novel “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” had long since entered the public domain in the early 1990s when Maguire was looking to write about the nature of evil. Its elusive witch was a promising canvas on which he felt he could explore complex questions of sympathy. The novel gives the Wicked Witch the name “Elphaba” and sees her growing disillusioned by the prejudice of Oz and its institutions in the years before her encounter with Dorothy Gale.

The iconic Broadway adaptation “Wicked,” which has experienced continued success since its 2003 premiere, keeps much of the novel’s moral commentary intact, which Maguire suggested was conditional for his approval of its adaptation.

“Those questions are essential,” said Maguire. “What do we actually know about evil as individuals? Is there any overlap between different conceptions of evil?”

Maguire made his embrace of the story’s theatrical nature clear throughout the course of the lecture by singing one of the musical’s iconic numbers, “The Wizard and I,” shortly after adopting the iconic affectation of Margaret Hamilton’s Wicked Witch from the 1939 film to recite a passage from his book.

Maguire detailed his extensive and varied journey in storytelling, as he published a number of children’s books and reimagined other classic fantasy stories in the years since “Wicked.” 1999’s “Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister” subverts the Cinderella story’s point-of-view, while 2015’s “After Alice” dives into the experiences of a minor character in Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.”

Nearly three decades after “Wicked,” Maguire is still drawn to the world of Oz. Following multiple novels in what became known as the “Wicked Years” series, Maguire published “The Brides of Maracoor” in October of last year, the first installment of a spin-off trilogy intended to focus on Elphaba’s green-skinned granddaughter, Rain.

“It’s sort of like what ‘Frasier’ was to ‘Cheers,’’ Maguire joked.

Similar to his initial inspiration to give Elphaba a story, his continued fascination with Baum’s world is only tangentially related to its fantastical qualities. To Maguire, the magic of Oz is an ongoing tool in exploring many of the same questions he was asking nearly three decades ago.

“As I’ve lived as an adult, I have not seen any delimitation of the instincts toward corrupt behavior on the part of individuals or organizations,” Maguire said. “Writing about this country of Oz, about a nation-state in paroxysms of moral confusion helps me survive the nation-state in which I live, which is experiencing many of the same concerns.”