California author joins Oxford community efforts to save the bees

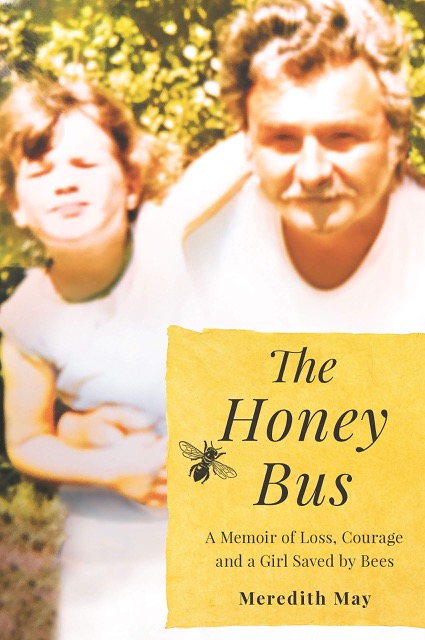

Photo provided by Meredith May

Author and beekeeper Meredith May speaks in Oxford Oct. 12 and 13.

October 8, 2021

The American Bumblebee has disappeared from eight states, including New Hampshire, Vermont, Idaho, North Dakota, Wyoming, Oregon, Maine and Rhode Island, according to an article from the Smithsonian Magazine.

While the bumblebee is still safe in Ohio, its population has declined by nearly 50% in the Midwest. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the species’ population has dropped nearly 90% overall, making them eligible for formal environmental protections.

Meredith May, fifth-generation beekeeper and author of “The Honey Bus,” will bring her expertise on the tiny, vital creatures to Oxford next week with an author chat and book signing, 6:30 p.m. Tuesday, Oct.12, at Lane Public Library, 441 S. Locust St.

That event will be followed by a panel discussion, “Mutualism with Pollinators,” 6:30 p.m. to 8 p.m. Wednesday, Oct. 13, in room 125 of the Miami University Psychology Building, 90 N. Patterson Ave., Oxford, sponsored by the American Library Association. Both events are open to the public.

May grew up around bees. After her parents separated when she was five, she moved in with her beekeeper grandfather. Thirty years later, she decided to start beekeeping again. The reintroduction of bees in her life inspired “The Honey Bus,” a memoir about the life lessons she learned from tending to the bees that lived in the old military bus in her grandfather’s yard.

“When I held bees again for the first time in 30 years . . . I knew then that it would take me a whole book to explain to people how much these tiny creatures mean to me,” she writes on her website.

The California beekeeper now advocates for bees and worries about threats to their populations from the effects of climate change and pesticides like Round-Up.

“It’s not any single thing, it’s all these things we’re doing together that are messing with bees,” May said. “The tiniest little creatures are going first.”

Climate change isn’t just affecting the bees; All kinds of pollinators are seeing their food sources dry up and die. This phenomenon has caused a 90% decline of monarch butterflies, too, May said.

May’s top concern is the Varroa destructor mite. This invasive species appeared in the U.S in the late 1980s. Once in a beehive, they multiply quickly, attaching to bees and sucking their body fluid, leaving them with a disease. These mites are becoming resistant to products like miticides, making them even harder to get rid of.

According to May, almost all managed hives get the mites at some point.

This attack on bees has a greater impact on the ecosystem, especially for humans, as nearly 70% of crops rely on pollinators, May said. Everything from the coffee we drink to vegetables at the supermarket rely on bees and other pollinators for fertilization.

How to help the bees

Despite the decline, there are some efforts being made to help the bees. May said the most important measure to prevent further population decline is to plant native wildflowers. She recommends using a Seed Ball, a preselected assortment of native seeds meant for easy dispersal of seeds.

“Don’t just plant them in obvious places like your own yard,” May said. “Go out into nature and throw them around, even in the medians or the side of the road.”

May also said to avoid pesticides at all costs and instead research organic forms of pest control. She also urged people who find themselves with a swarm of bees to call a local beekeeper to remove it without harming the bees.

Carla Blackmar, an Oxford resident of four years, planted a garden in a local effort to help pollinators.

Blackmar got into gardening to produce food and started to think about the possibility of feeding both her family and nature. After moving to Oxford, she had an opportunity to start a pollinator garden.

“The city ended up digging up a bunch of (my) land to do work,” Blackmar said. “One day they showed up with grass seed to “clean up” the lawn, and I asked them not to plant the grass and just leave the dirt.”

Blackmar’s neighbor’s also had a pollinator garden planted the same year by Songbird Environmental, an eco-scaping company in southwest Ohio.

Blackmar said it was a trial and error experience when she started planting her garden three years ago.

“I’ve tried all different things in the garden, it’s been really interesting,” she said. “You just have to be curious and it’s cool because there are so many plant ID apps to help.”

Local efforts are blooming

Blackmar said she aims to provide food for the pollinators throughout their active period by having something in bloom from early spring through fall. Right now, it’s goldenrod and aster season, two popular plants among the pollinators.

Photo by Stella Beerman

“We see European Honeybees, lots of cool native bees, wasps, butterflies and moths,” she said. “People don’t talk about our native bees because they aren’t as commercially useful, but they’re really important because they live in all kinds of complex ecological relationships.”

While Blackmar enjoys her garden, tending to it comes with its own set of challenges.

She has to make sure it isn’t overtaken by weeds or invasive plants and has to keep the deer from snacking on the bee’s food, too.

“Deer also really love our native plants,” Blackmar said. “I have tons of wacky little wire baskets I put over the plants to keep them out.”

But the most challenging part of the garden is finding greenhouses to buy plants that don’t use neonicotinoids. This chemical, applied to very young plants for pest control, acts as a neurotoxin to the bugs who later ingest it through the plant, Blackmar said.

She encouraged others to learn more about starting pollinator gardens with a few simple starter plants from Adopt-a-Plant, the Oxford Farmer’s Market, Prairie Moon Nursery or other verified distributors who don’t use neonicotinoids. Another option to avoid pesticides is starting your own plants from seeds, Blackmar said.

Blackmar recommended finding more information from Project Dragonfly at Miami University or the Cincinnati Zoo and checking out the butterfly garden outside Upham Hall on Miami’s campus.

To find a local beekeeper, visit “Beekeeping in Oxford Ohio.”