Miami hosts annual civil rights conference; City unveils marker

Descendants of two men lynched in Oxford in the 1800s help unveil a Reconciliation Marker, describing the murdered men’s stories, Monday, as part of the National Civil Rights Conference.

June 25, 2021

Miami University hosted the 10th annual National Civil Rights Conference in Oxford from June 20 through the 22, featuring several community-wide events focused on history, education and reconciliation.

The conference centered on the theme “Rise, Advocate, Educate and Cooperate: The Challenge of Change.” It was supposed to be held in Oxford last summer, but the pandemic postponed it until this year.

Miami University Archivist Jacky Johnson said she was grateful for President Gregory Crawford and the university’s support in hosting the conference. She also wanted to thank Interim Vice President of Institutional Diversity and Inclusion Anthony James for his efforts in bringing the conference to Oxford.

“The whole Miami community really came and supported it,” Johnson said. “We were the locals, but we needed everybody we had, people nationally and locally.”

Oxford was chosen as the location for the conference because of the Freedom Summer of 1964 program, where volunteers trained at the Western College for Women (now Miami’s Western campus) to be able to register Black voters in the south. Three of those volunteers — James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner — disappeared and were killed during that summer when they traveled from Oxford down to Mississippi.

On Sunday, June 20, a commemorative service was held at Mt. Zion United Methodist Church in Philadelphia, Mississippi to remember the three volunteers. Miami live-streamed the event for participants to watch at the Farmer School of Business Taylor Auditorium.

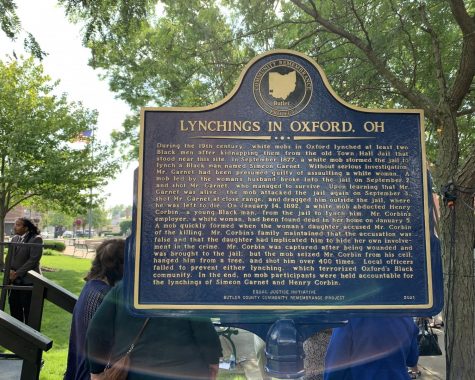

The 57th commemorative ceremony was technically a pre-conference event, with the first day of conference activities starting on Monday, June 21 with the unveiling of a new marker uptown, commemorating two Black men who were lynched by white mobs in Oxford during the late 1800s.

Oxford remembers the lynching victims of the late 1800s

“I know that there’s history, my family story, and somewhere in between, most likely, is the truth,” said Chris Corbin-Jerreals, the descendant of lynching victims Henry Corbin and Simeon Garnet.

Henry Corbin was a Black man who was lynched in Oxford Jan. 14, 1892. Simeon Garnet was lynched 15 years earlier on Sept. 3, 1877. Both men were killed without a trial by white mobs. Corbin was Corbin-Jerreals’ first cousin twice removed, and Garnet is the uncle of her grandmother’s first husband.

The marker was unveiled at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Park at 9 a.m. on Monday, as part of the conference. The project was co-facilitated by Director of Graduate Admissions Valerie Carmichael and Anthony James. The two worked with the Equal Justice Initiative to create the marker that would outline the stories of the two lynched Black men.

“This has been a substantial project and partnership,” Carmichael said. “It was extremely emotional for the family and for others. But it was worth it for the family members to see that the community has… started the learning, started the educating process, started reconciling our history with where we are today.”

Corbin-Jerreals, of Alexandria, Kentucky, was joined by other descendants at the unveiling ceremony. One of her cousins had to walk away, she said, because he was so upset.

“It was a very moving, wonderful, sad, reflective day. It brought me to tears,” Corbin-Jerreals said. “I guess I just felt bad because I felt like I was back there, when Henry was lynched. When they unveiled that marker with Sim and Henry’s story, it just brought me back to that day.”

Mayor Mike Smith, who supported the marker project along with the rest of city council, said he was struck by how one of the speakers at the unveiling said this “wasn’t a happy occasion, but a necessary one.”

“It’s a reminder of ‘never again,’ but with the events of the past 12 to 14 months, it also reminds you that we still have a long way to go on things,” Smith said. “We have to keep working, just constantly getting better. And I think it’s important that all our historic markers be somewhere people can see it and it means something.”

Now that Corbin-Jerreals has seen the story of her ancestors marked in Oxford, she hopes to mark their resting places as well. The two men were buried in unmarked graves, and Corbin-Jerreals is making it her new mission to find the spots and place something there to remember them by. It’s a small step among many to be made to remember those who were wronged.

“I hope people take away a sense that we never want to see it again. We need to be better people, we need to get along, and most of all we need respect for each other,” Corbin-Jerreals said. “I hope [the marker] makes people stop and think, and become better people — step up when they see an injustice, and do the right thing.”

Presenters spread awareness and knowledge

After the unveiling of the marker on Monday, conference attendees were shuttled to Shriver Center for several workshops and academic presentations. Talawanda High School graduate and Ohio State University student Ella Cope helmed one of those presentations.

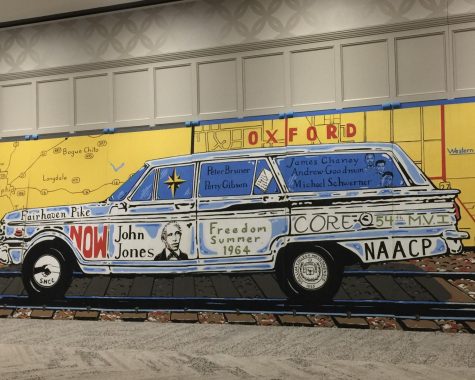

Cope facilitated the creation of the “Changemakers of Oxford” mural for her Girl Scout Gold Award two years ago. Until recently, the mural rested on the exterior wall of the Rittgers & Rittgers Law Firm, but it had to be moved when construction began on the lot right next to the law firm. Cope used the opportunity to present the mural in person at the conference. Plans are to move the mural to the side of the Oxford Municipal Building.

“I thought my presentation went really well,” Cope said. “It was really nice to be able to engage with an audience, and have my work and research well received.”

Cope used most of her presentation to discuss the finer details of her research process and the thought that went into each minuscule detail of the mural design. For example, designer Joe Prescher came up with the idea to outline the map of Mississippi on the mural in gray and outline the Ohio map in blue, to represent the Civil War uniform colors of each state.

By the end of her presentation, Cope was also touching on the role that public art plays in social movements.

“The main message of my speech was that art makes issues and ideas accessible,” Cope said. “And that’s why it’s necessary. The public art we’ve seen over the past year, especially in relation to the social movement of Black Lives Matter, has been impactful in a way that amplifies the message of the mural as it relates to racial violence, police violence and the lives of the victims of those crimes.”

In addition to presenting herself, Cope also attended every other session and workshop that was part of the conference. One Tuesday presentation that stood out to both Cope and Jacky Johnson was hosted by the Daughters Beyond Incarceration (DBI) group out of New Orleans, Louisiana.

DBI focuses on strengthening relationships between children and their incarcerated parents and providing resources for young women and girls. Four young women spoke at the conference presentation about building resilience and community support for children with incarcerated parents. Cope said the youngest presenter was 15 years old.

“I cannot overstate how amazing these women are. I was blown away,” Cope said. “I think it’s so fantastic that they are working amongst themselves to make spaces for them to be supported and heard. That was probably my favorite panel from the conference.”

Johnson said she also could not believe how young the presenters were and how personal the stories were that they shared.

“These weren’t scholars, these were just children,” Johnson said. “They were telling how it was to be a child with an incarcerated parent, talking about the prison pipeline for African American males. It was them telling their own stories, narrating their lives right to the conference attendees.”

The conference concluded Tuesday evening at the Shriver Center. Overall, more than 100 people registered for the event, and 15 people presented, according to Johnson. Smith was happy to see that the conference was well received in town from locals and visitors alike.

“I think [progressive change] is going to continue, with Oxford’s civil rights history. I think we’re going to continue to be a player, which is good,” Smith said. “And if they wanted to have the Civil Rights Conference here every year, I would totally be in favor of that.”