86-year-old Miami alumnae teaches violin to generations of Oxford children

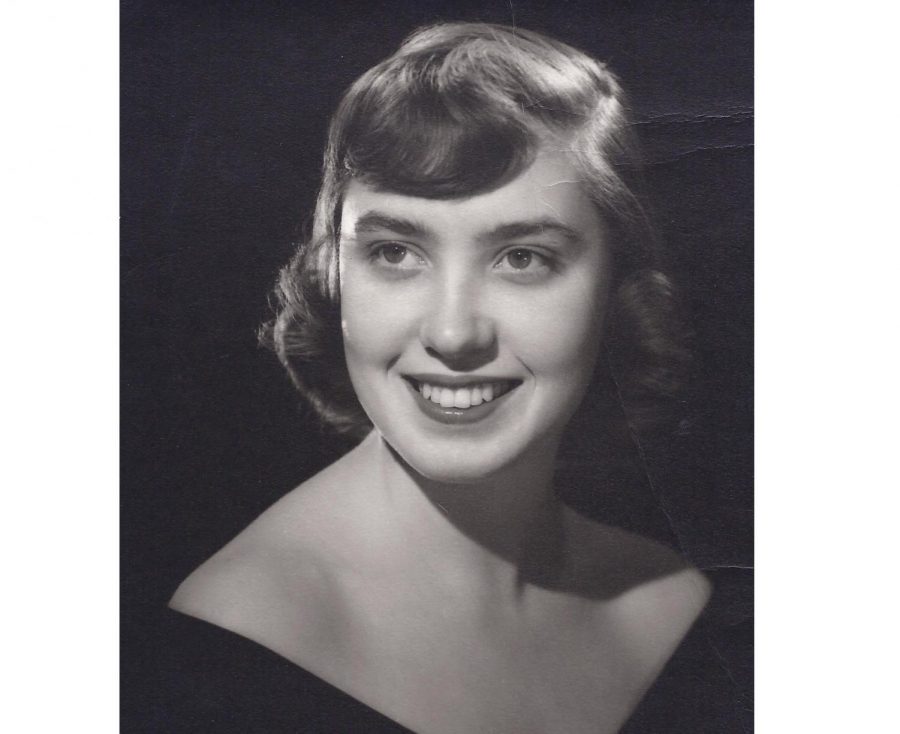

Photo provided by Lynda Herndon

Herndon and her violin in 2014.

May 6, 2021

Lucy Herndon has played the violin for nearly eight decades and has taught generations of Oxford children to play — and she has no intention to stop anytime soon.

Today, she still teaches at her private home studio in Oxford as part of Herndon Strings, her self-founded musical organization. When asked if she has ever considered retiring, Herndon said no.

“I want to teach until I die,” she said.

Herndon first learned piano. She then began playing violin when she was in fourth grade. She lived in Youngstown at the time, but moved to Cincinnati a year later and eventually began taking lessons. First in the Cincinnati public school system and then with an instructor from the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music (CCM).

Today, Herndon still remembers the names of all her instructors. “I just loved playing the violin,” she said. Though her parents started her lessons, Herndon was enthusiastic about music at an early age.

During her years at Cincinnati’s Withrow Junior High School, Herndon played with the senior high orchestra. In her senior year of high school, she was invited to play alongside college students in the CCM orchestra. Though Herndon wanted to attend CCM, women at the time could only teach privately and only men were allowed to play in the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra.

In high school, Herndon’s goal was to join Phil Spitalny’s All-Girl Orchestra, a group of women from the ages of 17 to 30, that Spitalny started in 1934. When the orchestra dissolved before she graduated, her parents pushed her to pursue a degree in elementary education at Miami University.

Herndon earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Miami and became part of three generations of her family to attend Miami, including her mother, her sister, and eventually her two daughters.

Despite Herndon’s present enthusiasm for teaching, she initially wanted to play in a professional orchestra. However, there were few opportunities for female musicians in major orchestras at the time.

“There was no place for a woman to play in an orchestra. And I wasn’t good enough to be a soloist, I knew that,” Herndon said.

“Back then, women could be a secretary, nurse, or a teacher,” Herndon’s daughter, Lynda, said. “And so, mom chose to be a teacher.”

Herndon went on to teach in Long Beach, California, and Mount Healthy, Ohio, before teaching for more than 30 years at Fairfield North Elementary School in Butler County.

She also began to play in multiple local orchestras around that time, including the Butler Philharmonic (previously known as the Hamilton-Fairfield Symphony Orchestra), Middletown Symphony Orchestra and the Southwest Ohio Philharmonic. She also became involved with fiddling, a more upbeat and country style of playing. She continues to be a member of both the Butler and Southwest Ohio Philharmonics.

In 2017, Herndon was honored for 60 years of playing in the Butler Philharmonic. For the occasion, her two daughters commissioned a stained glass panel for Herndon that featured a violin.

“We discovered midway through the project that the creator was the granddaughter of Adon Foster, who was concertmaster of the Dayton Philharmonic, a Miami violin professor, and Mom’s orchestra conductor when she was at Miami,” Lynda said. “A full circle Oxford moment!”

An advocate of the Suzuki method

As a parent, Herndon began her children’s musical education at a young age. Lynda said it was always a given that she and her sister would learn violin.

“Mom was loving and disciplined, but a perfectionist,” she said.

Lynda distinctly remembers Herndon’s emphasis on the Suzuki method.

“It was the 70s and the cusp of the movement,” she said. “I didn’t realize until later that we were at the very beginning of it.”

Pioneered by Japanese violinist Shinichi Suzuki, the teaching method centers on an early beginning to violin purely based on ear-training and listening ability. After constant repetition and learning pieces by ear, children eventually move on to read music.

Herndon started her daughters’ violin lessons based on the Suzuki method when her elder daughter, Lynn, was 8 and Lynda was 4.

“I never learned to read music until I was 8,” Lynda said. “I was listening to everything instead and putting in fingerings for the notes. I was on book four or five out of 10 before I started reading notes.”

“I was able to take my girls all over the world with the Suzuki method,” Herndon said.

Together, she and her daughters traveled to Suzuki institutes in Tennessee, Washington, D.C. and Wisconsin, as well as international conferences held in Hawaii, Massachusetts, Germany and Japan.

“Attending these truly changed my life,” Lynn said. “I made many friends and learned from amazing teachers, all because my mother believed in learning and studying music.”

Herndon said the conferences had a lasting impact on her.

“I had never seen so many people playing violin in my life, and I had never seen so many people so interested in strings,” Herndon said.

She credited this interest to Suzuki, whom she met on multiple occasions.

“He was a gentle man, and he was always willing to learn when he came upon new techniques for holding the bow or positioning your fingers,” Herndon said. “He was really wonderful and very human.”

Suzuki’s ideas greatly shaped Herndon’s philosophies about the violin.

“Mom used to tell us, ‘practice makes perfect. Suzuki would say if you don’t practice, you don’t eat,’” Lynda said. “Anywhere we traveled, we had to take the violin, even if we were going to the beach.”

Lynda recalled one memorable instance when she wanted to switch to playing cello, but Herndon refused.

“Mom said then we would have to buy an extra seat for the cello on the airplane,” Lynda said. “With a violin, we could just put it in the overhead.”

Lynn added that her mom always knew what to do on stage and how to navigate the musical world.

“Once I was playing a solo on stage at a Middletown Youth Symphony Orchestra concert and my E string broke,” she said. “Instead of taking the time to put a new string on, Mom ran to the stage and told me to borrow another violin to finish my solo.”

Because Herndon was so focused on music and had been unable to pursue her career as a performer, Lynda said she felt like her mom, “lived vicariously through my sister and me.”

“I felt obligated to go into performance and music, and I remember that when I was in high school, I came to my mom crying and asked if she would be upset if I majored in business, not music,” said Lynda Herndon. Her mother told her she could pursue any career path she wanted.

The family’s musical legacy continues

Herndon’s entire family continued to be musically involved. In 2016, the Ohio Federation of Music Clubs honored them with the “Musical Family of the Year” award. This encompassed three generations of Lucy Herndon, daughters Lynn Denney and Lynda Herndon, and grandsons Nicholas and Ian Denney.

Lynn teaches fourth through eighth-grade orchestra at Wyoming City Schools. Both Herndon and daughter Lynda are affiliated with Miami’s Virginia Pearce Glick Young Musicians’ Program, which provides violin, viola and cello instruction for young string players in Oxford.

Christine House-Shumway, director of the program and a private violin instructor, said that before becoming friends with Herndon, she already knew of her.

“When I moved to Oxford, I didn’t know her directly,” House-Shumway said, “but I did know she was teaching a whole bunch of young students Suzuki. I was impressed that her students all had good hand positions and good posture.”

House-Shumway also indicated her enthusiasm for Herndon’s work with younger children. “I’ve definitely learned from her,” House-Shumway said. “Lucy has all the cute little songs and works hard for kids to develop good technique and to bow correctly and respect the audience.”

“The idea of teaching kids by ear is wonderful when you’re starting them out with the coordination of a string instrument. It’s easier to pick up things by ear, like a language,” House-Shumway said.

Sofia Bolda started the Suzuki method when she began taking private lessons with Lucy in the seventh grade.

“Lucy is somewhat blunt when she’s teaching,” Bolda said, “but that really helps me understand what I need to do.” Bolda said that for her, a memorable moment with Herndon occurred just recently.

“In March, I played at the Junior Violin Festival with Lucy as my accompanist,” she said. “We were practicing together about a week or so before the competition, and I just remember her telling me that I’ve come such a long way and I’m playing really well. It really meant a lot to me.”

Bolda, an incoming freshman at Miami University, will major in music education. She is also considering a degree in performance.

“A big part of the decision was having teachers like Lucy who pushed me, supported me, and taught me,” Bolda said.

“Lucy always tries to make her students feel special and loved,” Judy Bohne, who first met Herndon through the Ohio Federation of Music Clubs about 30 years ago, said.

“When we had our violin festival at Miami, after the children played, Lucy would always give them a rose. I don’t think any other teachers do that,” Bohne said. “And if Lucy says she’s going to do something, she does. She’s a trustworthy and generous person.”

House-Shumway also expressed her admiration for Herndon.

“Over the last couple of years, I’ve gotten to know her more. She’s in her 80s and she’s a pretty modern thinker. And she’s very strong,” she said.

There’s no reason to stop playing

Despite the pandemic, House-Shumway said, Herndon has not stopped staying active.

“COVID has stopped a lot of people, but she’s still living life. If the orchestra called her and asked to go play, she would go play. She’s not going to stop because of COVID, she’ll put her mask on and go. She’s still teaching in person,” House-Shumway said. “I admire people that live. There’s a lot of people her age who have sat down in front of the TV and stayed.”

“When my mom sets her mind to do something, it’ll get accomplished,” Lynda said.

She added that she’ll always think about Herndon’s passion for violin. “All her life, everything has been about the violin. Her life revolves around music,” she said.

Lynn recalled that once, when leaving the stage from a concert at Miami, Lucy tripped over the back of a stage sound shell and injured her head.

“She told me she knew she was falling but didn’t have time to put her hands out to catch herself,” Lynn said. “When I asked her what she was doing instead, she said: ‘I was protecting my violin, of course! I saved it from being crushed!’”

Herndon laughed as she recounted a hard-won backstage meeting with Donny Osmond from the Osmond Brothers musical group. When Osmond learned that Herndon was considering quitting the violin after she turned 80, he said, “don’t you quit playing. You play until you die!”

Herndon, now 86, didn’t quit. “Music is my salvation,” Herndon said. She tries to convey this love to her students through her teaching.

“It’s wonderful to see her take a student from the beginning and watch the growth as they advance, both on the instrument and in relationship,” said Lynn. “Slow and steady, she gets the job done.”

“I just want my students to love the violin like I do and to enjoy it, not to be a big orchestra player or a soloist,” said Herndon. “I try to live by what Suzuki said: music gives you beauty of the heart.”