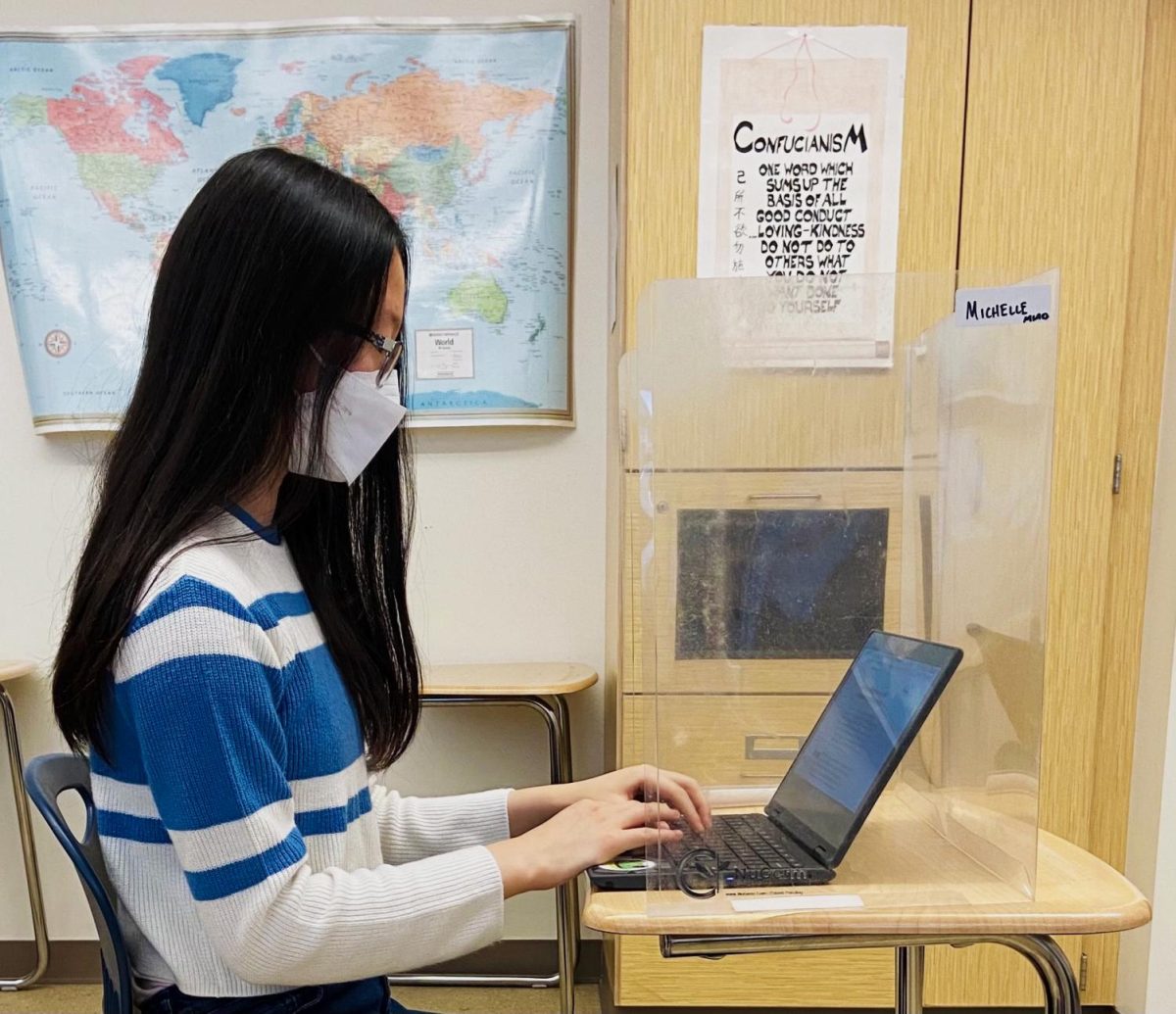

Face masks and plastic shields are new normal at Talawanda

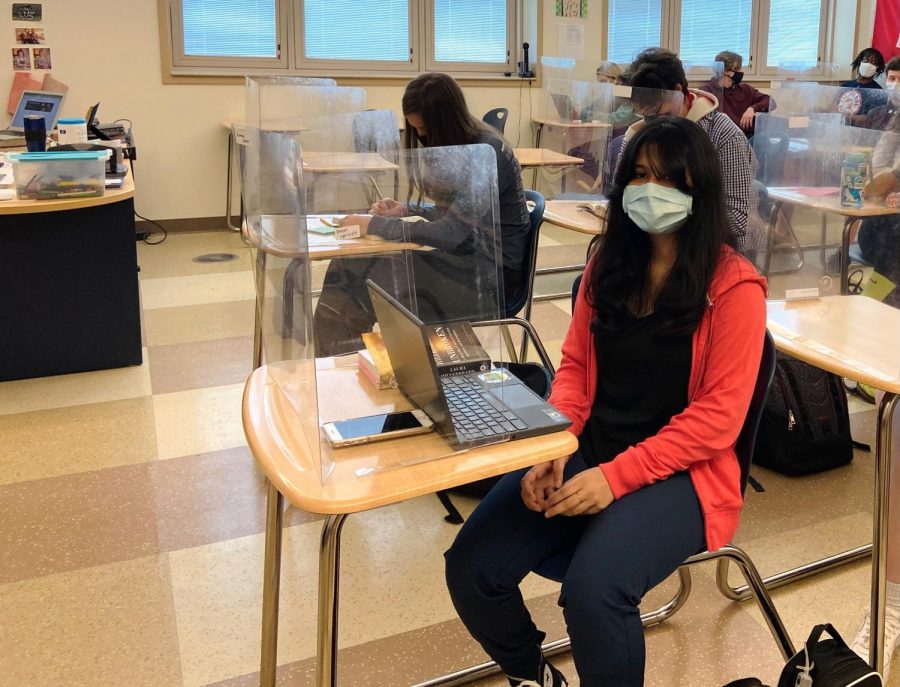

Writer Michelle Miao sits behind plastic shielding at her desk at Talawanda High School. The shields are part of the new normal of going to school. Students at the school were forced into remote learning twice this school year, but have been back in school since January.

March 12, 2021

In January, Talawanda School District students stepped into classrooms after two shutdowns, in which the district expanded its family support network but saw students struggle with virtual instruction.

Talawanda first shut down in March 2020, under orders from Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine. It shut down again in November after the number of quarantined staff rose too high to provide students with essential services. The district resorted to online classes for the rest of the fall semester.

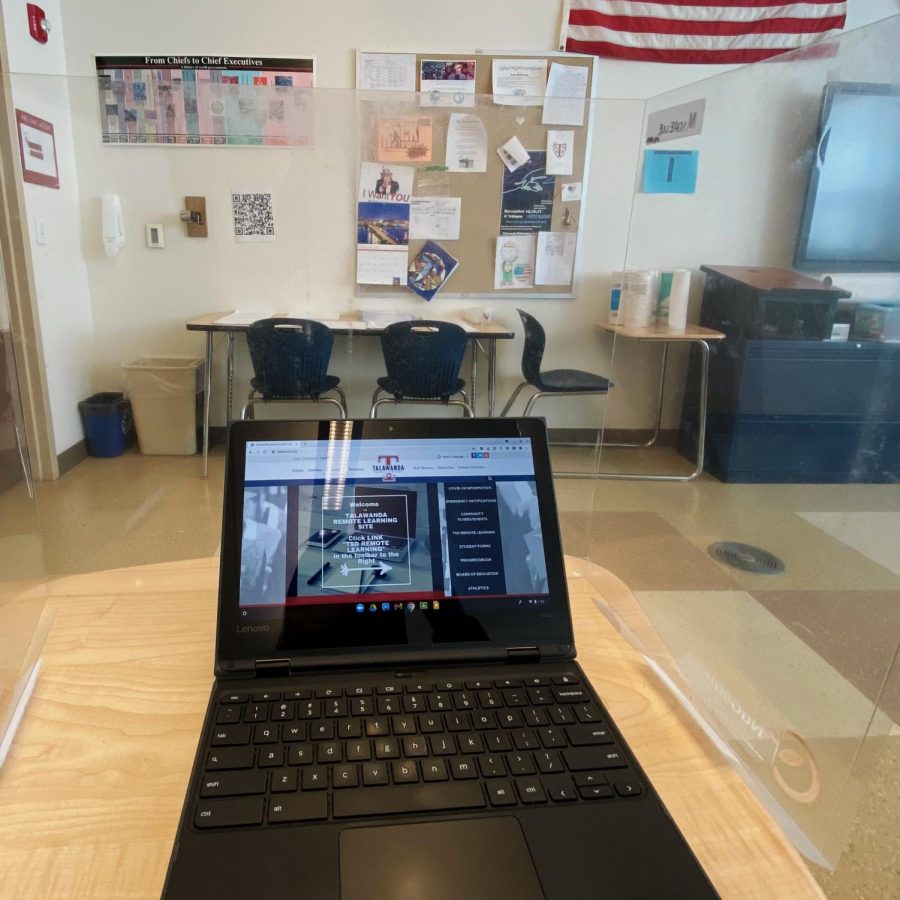

Currently, Talawanda Middle and High Schools operate in-person four days a week, with Wednesdays designated as an asynchronous day – which means students do previously assigned work at home.

The elementary schools are in-person five days a week. All students were given a chance to choose virtual classes at the start of the spring semester and, as said by Talawanda Superintendent Ed Theroux, about 20% of students remained fully online.

At school, students and staff wear masks and students carry foldable plastic shields that are set up as screens on their individual desks.

The shutdowns forced adjustments to virtual classrooms under the added stress of the pandemic. Many families, Theroux noted, experienced financial difficulties, some for the first time. A September 2020 NPR/Harvard poll found that nearly half of American households have faced job loss or experienced pay cuts throughout the pandemic.

To help families in need, Talawanda started a weekly food distribution program. This program, assisted by the federal government, will continue until the end of June. Talawanda staff also deliver food to families who can’t pick up packages. In addition, school resource officers set up hotspots for students without internet access.

When virtual learning began, teachers across the district reported poor Zoom class engagement. Some students could not sign in to class or failed to complete assignments. In some cases, school counselors and resource officers conducted “wellness checks,” to develop individual plans with students who needed extra assistance or whose caretakers lacked skills to help.

The switch to online learning proved difficult even for students who came to class. A study by Boston University concluded that about 30% of high school students nationwide felt more depressed due to distance learning.

Theroux said that throughout this experience Talawanda parents have been chiefly concerned about the mental health impact of the pandemic on students. Talawanda High School junior Julia Peter labeled the changes as “stressful.”

“There was a lack of stability. With most of my teachers, it seemed like they had a lot of trouble because it’s really hard to stay motivated when students aren’t interacting,” Peter said.

Peter is a member of Hope Squad, a peer-to-peer suicide prevention program. She said Hope Squad sent out a survey to high schoolers that asked about their stress levels.

“We asked about how stressed they are on a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 being super-duper stressed, and the average score was an 8,” Peter said.

For students at the elementary level, developmental concerns have been raised. Rob Rucker teaches second graders doing virtual learning at Kramer Elementary, in Oxford. He said he appreciates the virtual option but it also hinders students’ ability to socialize.

“I believe it is important that students get social exposure to learn and interact with their peers,” said Rucker.

Theroux is hopeful that this normalcy can resume in the fall. Despite the turbulence of the past year, Rucker remains optimistic.

“There is a light in the tunnel,” Theroux said. “Next year, I am hoping and praying that we will be open in person.” For students, Theroux holds a similar confidence.

“Our students are resilient,” Theroux said. “They catch up quicker than we may think, and for those that don’t, it’s all about putting pieces in place to help them.”

Theroux acknowledged that the current situation isn’t perfect, but said Talawanda is trying its best to accommodate the needs of all students and families. When asked about the most important takeaway from the pandemic, Theroux stressed the need for flexibility and patience.

He also pointed to what he views as a positive side of remote learning. “For over 200 years, public education kind of looked the same,” Theroux said. “Kids in desks, teachers in the front.”

Now, however, he predicts that the next generation of students and teachers will have new technological skills firmly in their grasp.

“That’s what we want, and that’s going to help prepare us for the future,” he said.