Campus closure saved energy; Miami plans more energy savings for future

Miami’s campus, usually busy with students, sat mostly-empty for the early month of the COVID-19 pandemic.

November 25, 2020

Miami University closed its campus Wednesday, March 11 as the outbreak of COVID-19 forced shutdowns across the nation.

The normal bustle of college life was quickly replaced by eerie quiet. Students went home. Parking lots were mostly empty and most buses no longer ran. No one roamed the hallways and campus buildings were locked up.

Meanwhile, Miami shrank its carbon footprint by turning off lights and turning down the heat.

Cody Powell, Miami’s associate vice president of facilities planning and operations, said Miami acted to strategically limit its utilities use while the campus sat empty.

“We were fairly aggressive about understanding what type of operations were going to continue in certain buildings and which buildings would have very few people in them,” Powell said.

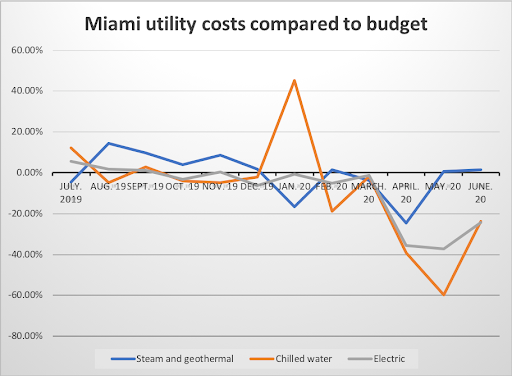

Powell said it’s difficult to say exactly how much energy Miami saved because weather plays a major role in how much energy is used. But Miami’s bill shows over 20% in savings on chilled water and electricity in April, May and June.

The savings came not only because of absent students, but also as a result of planning by the university.

Powell said Miami officials have daily meetings to develop building automation programs that save energy by looking at how and when Miami’s buildings are occupied — these meetings were not necessary in the past. Powell said his staff created customized energy plans for buildings based on their occupancy, which consider which facilities are being used.

“If the building isn’t being used then we’re trying to save as much energy as we can,” Powell said. “It’s become very customized just based upon the scenario that we’re in and all the change and all the ways our buildings are being occupied.”

Adam Sizemore, Miami’s director of physical facilities sustainability, is the co-chair of the university’s climate action task force which is developing a path for Miami to become carbon neutral.

Sizemore said the campus shutdown also helped Miami reduce its consumer waste, such as uneaten food in dining halls.

David Prytherch, professor of geography and chair of the subcommittee on transportation on Miami’s climate action task force, said Miami reduced its transportation emissions in the spring by eliminating bus routes that weren’t necessary.

“Ever since March, buses have been on a somewhat reduced schedule… Definitely there were fewer people on campus and fewer routes,” said Prytherch, who also is a member of Oxford City Council.

Energy costs associated with reopening

Despite Miami saving energy when campus was closed, it faced some sustainability challenges when it reopened. To prevent the spread of COVID-19, Miami upgraded to MERS-13 air filters, which require additional energy to create pressure to push air through the filter. And Miami adjusted its ventilation settings for buildings to limit recirculation and incorporate more outdoor air, which increased the energy required for heating and cooling.

Powell said the estimated cost of the changes is a $400,000 increase in energy usage.

“The strategies we’re using to keep people safe are definitely causing us to use more energy than we would otherwise,” Powell said. “It hurts our sustainability initiatives, but that is what it is. We’ve changed those strategies to increase the amount of fresh air.”

Powell added that $400,000, while substantial, is a small amount compared to Miami’s total energy bill.

Additionally, Miami dining services started using single-use plastic utensils, packaged condiments and paper takeout trays in response to COVID-19 sanitation guidelines. Sizemore said these adaptations to help prevent the spread of infection do increase waste, however.

“That’s kind of the tradeoff you have sometimes between sustainability and being resilient,” Sizemore said.

A greener future at Miami University

On Sept. 22, Miami President Gregory Crawford signed Second Nature’s president’s climate leadership commitment which commits Miami to developing a plan with goals for community resilience within two years, and a plan for carbon neutrality.

Susan Meikle, Miami’s news and communications editor, said Miami will develop its campus-community resilience assessment by Sept. 2022 and then create a comprehensive climate action plan by Sept. 2023 and set a target for achieving carbon neutrality.

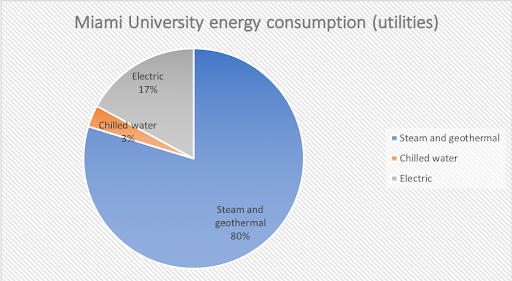

Meikle said Miami’s carbon commitment has been a 10-year process starting with Miami’s utility master plan which began moving Miami off steam to reduce the university’s fossil fuel consumption and water use. Meikle said that by fall 2020, nearly half of Miami’s campus buildings were converted to electric heating and cooling, and in 2019 emissions were reduced 51% compared to a 2008 baseline.

Sizemore said he thinks people can learn from the COVID-19 pandemic to help build a more sustainable future by continuing to have virtual meetings and workdays at home, which eliminate transportation emissions.

“Very quickly the entire world became experts in Zoom and Google Meets and I think we can learn from that and take that mastery level that we’ve developed to utilize it on a day in and day out basis… And I think I can see myself still doing this.”

Prytherch echoed those thoughts. “COVID has taught us that telecommuting can be pretty functional.”

Last year, Oxford signed onto the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, which strives to lower emissions and build climate resilience.

Prytherch said he thinks Miami and Oxford’s commitment to energy initiatives should be collaborative. Oxford’s League of Women voters hosted a virtual meeting Nov. 18 for representatives from the university and the city to discuss how the two can work together to achieve sustainability goals.

“Obviously we’re deeply interconnected so we’re trying to make these parallel processes lead to the same place,” Prytherch said. “We’re trying to coordinate those two processes the best we can… And we’re really hoping in the end that it’s one joint initiative.”

Prytherch said carpooling, electric car stations and encouraging walking and biking are ways transportation can be made more sustainable locally.