The Talawanda School District received an F grade for student preparedness on the most recent Ohio Department of Education report card.

That sounds bad, but Talawanda teachers and staff say the failing grade is because the state uses the wrong data to measure whether students are prepared for their futures.

The annual report card, released last month, ranked districts in six categories to assign an overall letter grade. In this year’s report card, which is based on data from the 2015-16 and 2016-17 school years, Talawanda drew a B overall, but an F in the measure the state calls “Prepared for Success.”

“We don’t believe the title of ‘Prepared for Success’ is accurate,” said Talawanda director of teaching and learning Joan Stidham. The district, she said, doesn’t think the numbers the state uses are “good measures for all of our students.”

Talawanda is hardly alone in failing the “Prepared for Success” measure, which the state says “looks at how well prepared Ohio’s students are for all future opportunities.”

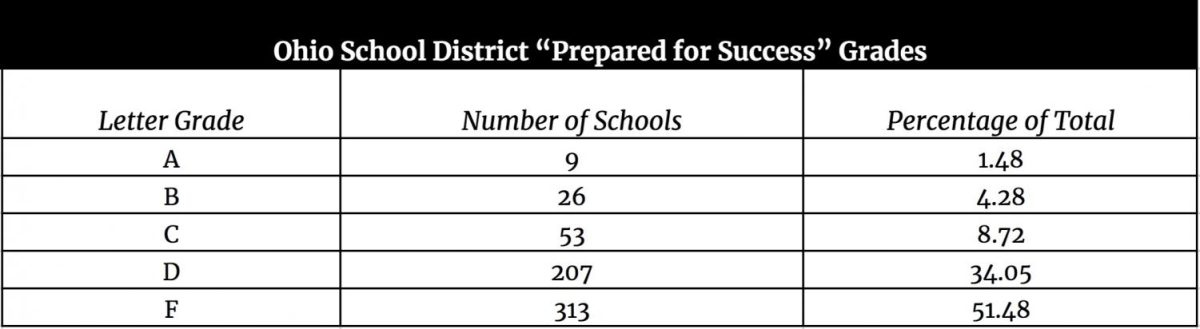

Of the 608 school districts in Ohio, only nine scored an A in “Prepared for Success.” Talawanda was among 313 districts given an F in “Prepared for Success.” Another 207 earned Ds.

State Changed the System

Chris Woolard, the Ohio Department of Education’s senior executive director for accountability and continuous improvement, said the low grades are a result of changes in the grading scale the state uses to evaluate districts.

The state introduced “Prepared for Success” in 2016, and Woolard said the Board of Education has been adjusting the standards for the measure since.

“They are drawing lines on what it takes to get an A or B or C. When you get a lot of schools that are getting a lot of Ds and Fs, you want to reflect on what’s happening, what’s being counted, what are some of those decisions,” Woolard said.

The fluctuation in the grading scale, Woolard said, makes it difficult to compare districts’ results year over year: While 313 districts received an F in “Prepared for Success” this fall, only 90 did so on last year’s report card.

The formula the state uses to calculate the metric is complex. Districts are given one point for each student who earned a remediation-free score on the ACT or SAT, an honors diploma, an industry-recognized credential, or any combination of the three. An additional 0.3 points are given for each student who also earned a 3 or higher on at least one Advanced Placement exam, a 4 or higher on at least one International Baccalaureate exam and/or at least three college credits as a high schooler.

The district’s point total is divided by the number of students who graduated in the two-year period the report card uses, to get a percentage that’s converted to a letter grade.

Refinements Continue

Woolard said while “Prepared for Success” is intended as an “aspirational measure,” the state is continuing to refine what goes into that measure. Several working groups preparing to make recommendations to the legislature, and districts could soon receive credit for their students’ military readiness – measured by the ASVAB – and internship or apprenticeship credit.

Such changes, Joan Stidham said, would be welcome at Talawanda, where external factors prevented a greater number of students from earning the district points in preparedness. Industry-recognized credentials – certifications in areas ranging from CPR First Aid to Adobe Photoshop – are only available through the district’s career-technical partner institution, Butler Tech.

Few students pursue an honors diploma, Stidham said, because there’s no incentive to do so other than a seal on their diploma. In other states, earning an honors diploma qualifies a student for scholarships and financial aid for college.

A Student’s View

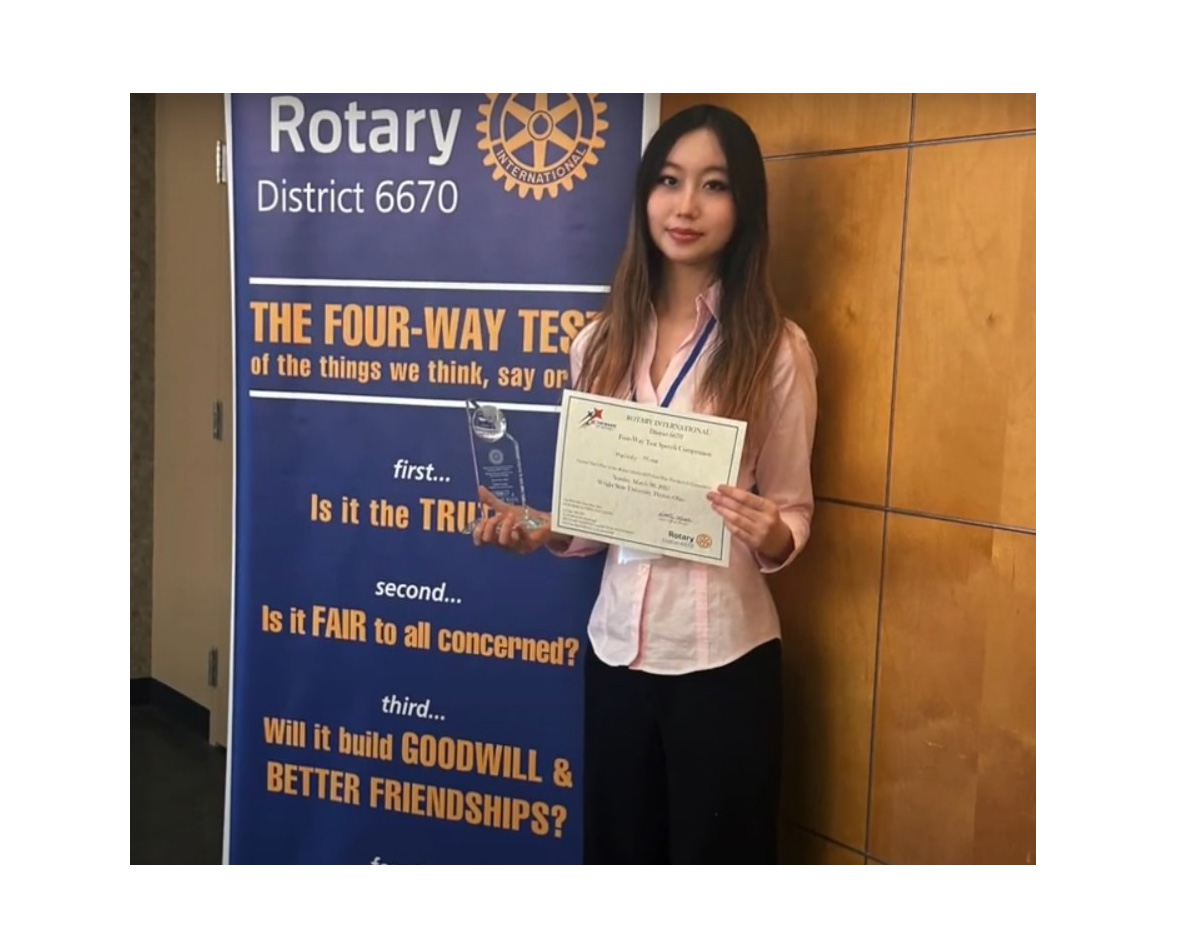

Recent Talawanda High School graduate Charis Whalen said that her experience was that the district focused resources on high-achieving students who were more likely to pursue advanced classes. The district devoted less attention to vocational students and those who were not college-bound and might pursue industry-recognized credentials, she said.

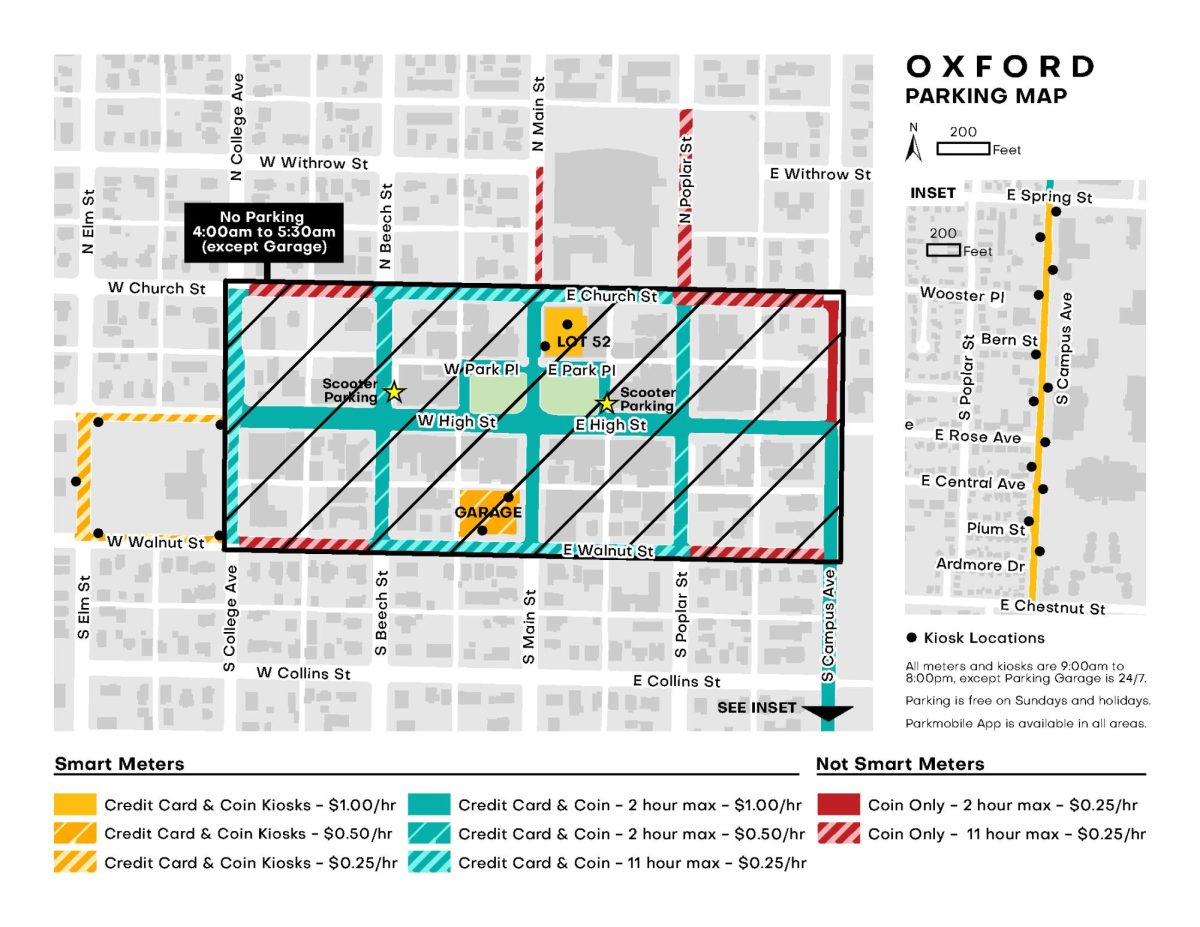

College-bound students can take Advanced Placement, honors, or College Credit Plus courses – an option bolstered by the district’s proximity to Miami University – while students planning to enter the workforce after graduation are largely limited to Butler Tech courses.

“There was more attention given to the honors students and students who were academically advanced” as opposed to those on a vocational track, Whalen said.

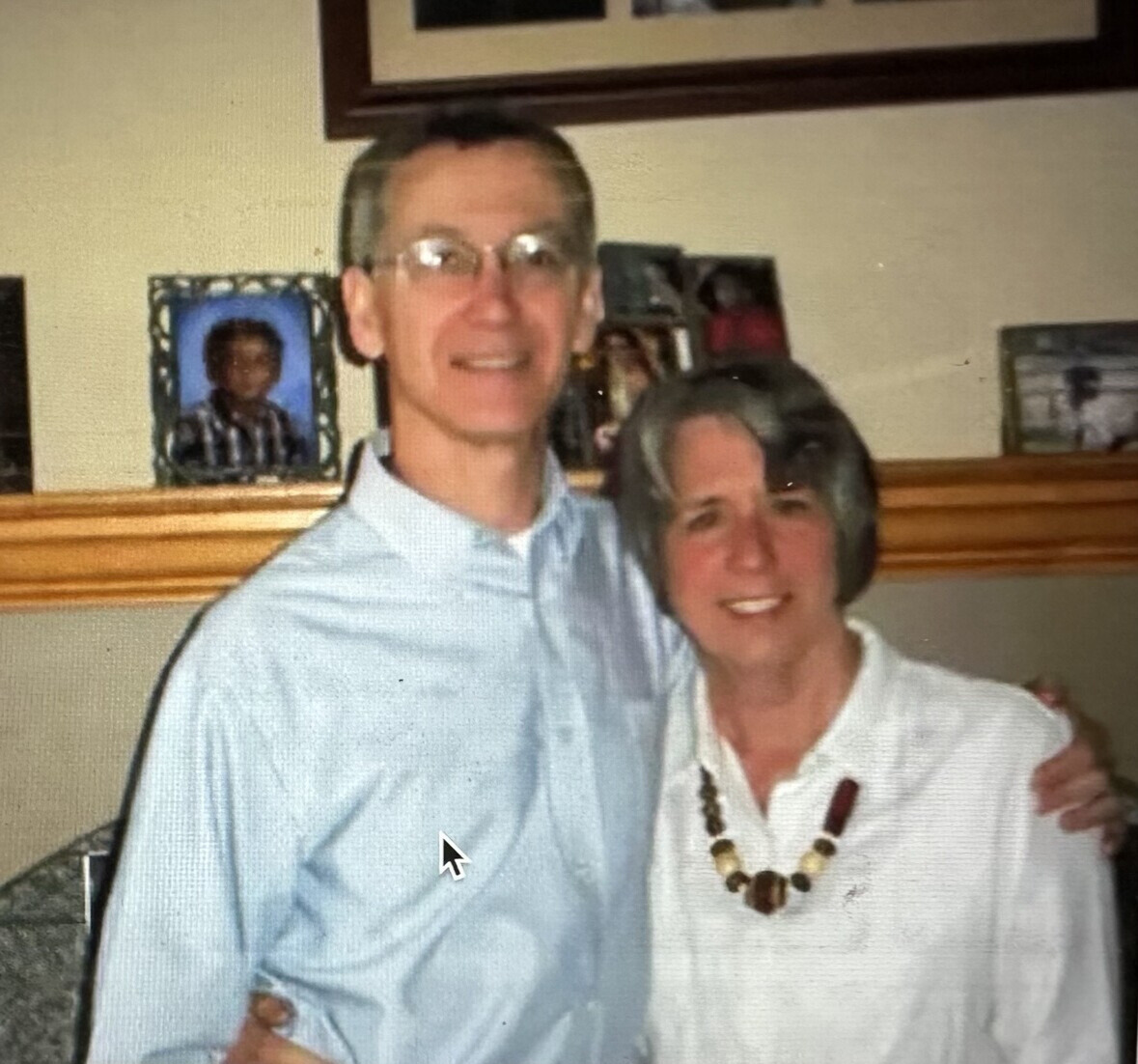

Amanda Weatherwax, who teaches English and journalism at Talawanda High School and is the mother of one Talawanda graduate and another current student, said the factors the state considers in the “Prepared for Success” grade aren’t the sole indicators of a student’s readiness for college or the workforce. While she and her fellow teachers “wonder” about ways to bolster the district’s “Prepared for Success” score, she said she doesn’t consider the F grade a reflection of the work she or her students do.

“I would never want a parent to look at that [grade] and think that that reflects the preparation their child has had,” Weatherwax said. “They may not have scored on this particular state measure, but when it comes to what really, really counts, I think that they’ve been prepared.”