How should we teach students about something as controversial and as rancorous as the recent impeachment and subsequent acquittal of President Donald Trump? Whether you favored the impeachment or supported the president, there is no denying that it was a significant event in the nation’s history.

As the presidential impeachment process had happened only twice before, history teachers and professors didn’t have a prewritten set of lesson plans or curriculum standards to use in the classroom, but that didn’t stop the discussion.

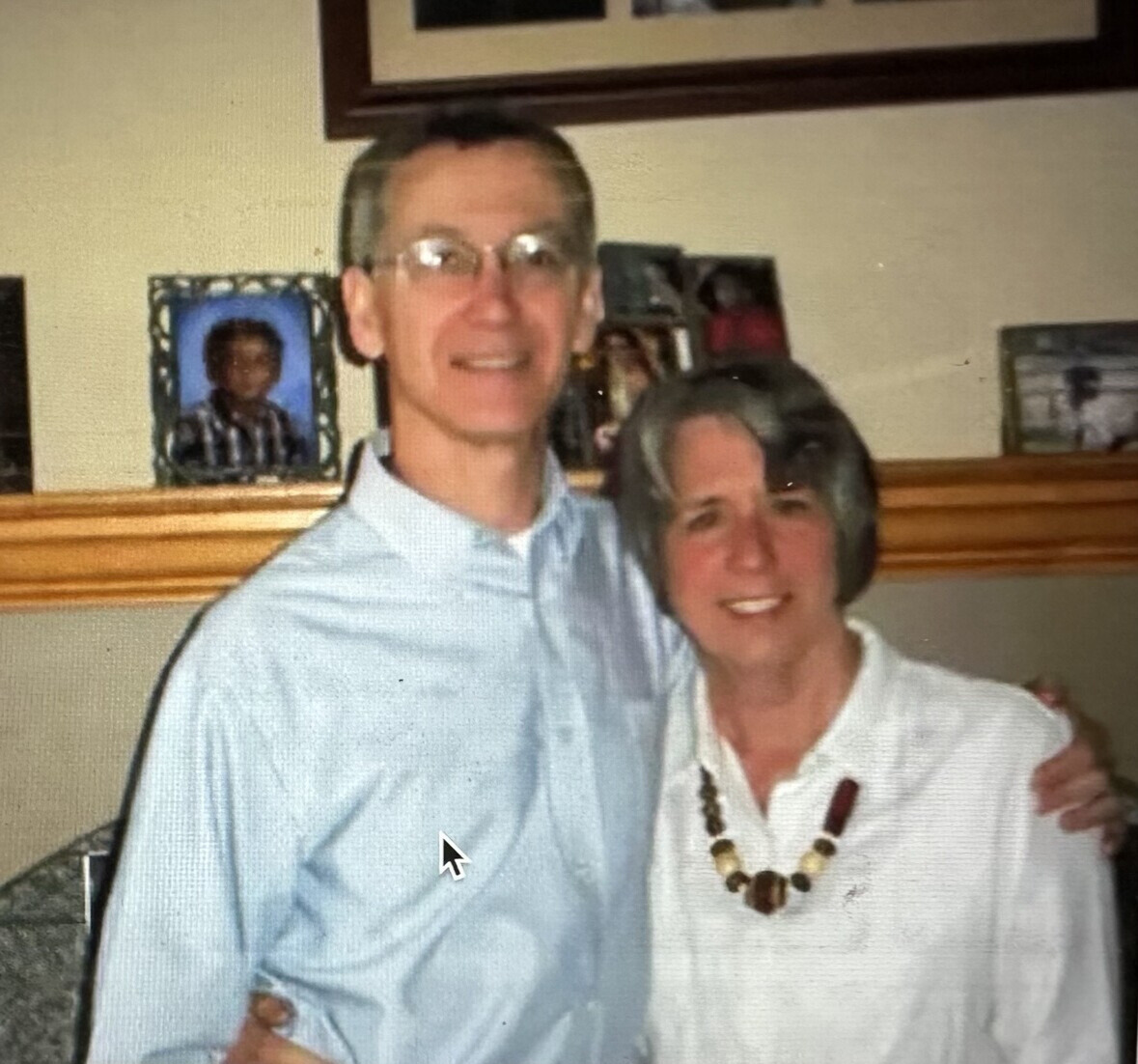

For Ted Caudill, chairman of the Social Studies Department at Talawanda High School, the topic of impeachment came up every day. It began with the U.S. House of Representatives’ inquiry into Trump’s infamous telephone call last July 25 with Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky, and ran through the trial in the Senate trial that began Jan. 16 and ended with his Feb. 5 acquittal on charges of abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.

Caudill teaches mostly freshmen who had many questions — and opinions — about the inquiry and trial. Most questioned why political partisanship had mattered throughout the months-long process. In discussion, Caudill worked hard to give an equal platform for both sides of the issue.

As the students are still developing their own political identities, Caudill emphasized the need for mutual respect and understanding.

“Whatever you have to say is valid,” he tells his students. “But you have to be able to respect the person that disagrees.”

Gaining understanding through discussion

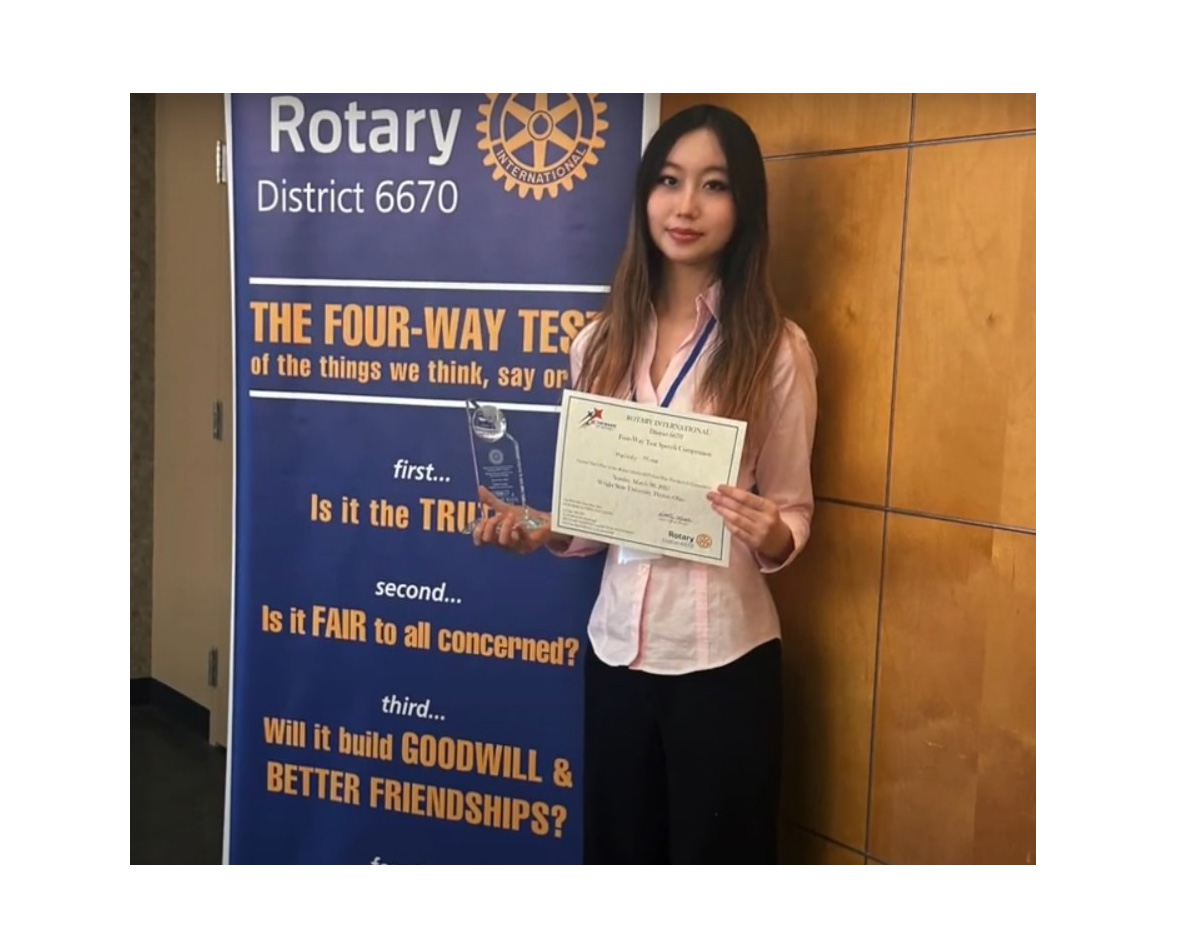

Maia Sepiashvili, a senior at Miami University majoring in political science and economics, didn’t have a strong opinion on the impeachment and appreciates the understanding she has gained from other students’ opinions in her political science capstone course, “Executive Power During Trump.”

The students in the class continue to examine the impeachment trial’s effects on current events, such as the State of the Union address and election campaigns.

“By hearing other people’s opinions, maybe it will give me a better scope of how this affects the masses,” said Sepiashvili. “It affects me differently than it affects other people.”

Thomas Misco, professor of social studies education at Miami, teaches his education students various tactics to push their own students to be able to defend their opinions. As a former high school social studies teacher himself, Misco believes that the impeachment trial should be “front and center,” of all social studies classes right now.

“We view politics as seeing something personal, or private,” said Misco. “It’s not private at all –it’s extremely public.”

Sepiashvili agreed, and believes that impeachment will “inevitably” continue to be discussed in her classes.

“This affects a whole nation of different kinds of people,” she said.

Giving structure to controversy

Misco recommends two strategies for building educational curriculum around the subject of the impeachment trial. The first is a structured academic controversy, where students take editorial opinions from both sides of an issue, choose one for which to argue and then switch to argue the other side.

His other preferred method is a technique of deliberation where he asks the class to do the majority of the thinking and probes them with questions and conflicting evidence so that students work to defend their opinions.

Caudill employs a similar technique. Rather than disclose his own political affiliation or impeachment opinion, he uses open-ended questions to push students to develop their own perspective.

Sepiashvili appreciates teachers who use this apolitical technique in classrooms. “They’re the ones deciding my grade in that class,” she said. “It just makes it a lot more complicated.”

When a professor is open about a political affiliation that is opposite of hers, it causes her to participate less in class, she added.

These discussions, especially about a process as rare as impeachment, are valuable, said Caudill. “The impeachment trial has given us an incredible opportunity to develop critical thinking skills. The whole thing is not only new to them, but new to the country.”

Misco agreed that it is important to not shy away from these tough conversations, and that impeachment should be discussed in all social studies classes. “We ignore the present at our own peril,” he said. “The most dangerous thing would be to leave these topics outside the school door, and discuss only at home.”