Ohio’s license plate blunder renews call for history education

November 5, 2021

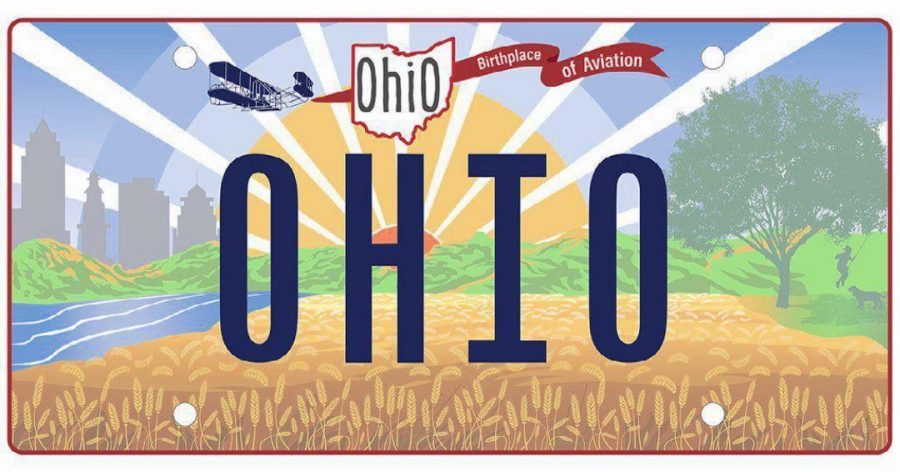

On Oct. 21, Ohio’s Bureau of Motor Vehicles unveiled its revamped design for state license plates. The new design, “Sunrise in Ohio,” is a riot of symbolism. Inspired by the Great Seal of the Buckeye State, the imagery includes a stylized sun rising over low-slung hills and a field of yellow wheat, flanked by an urban skyline and the silhouette of a child playing on a tree swing, accompanied by a friendly dog. Completing the picture, the iconic Wright Flyer takes to the skies, pulling a banner proclaiming the “Birthplace of Aviation.”

“We wanted Ohio’s new license plate to reflect the heart and soul of our state and to encapsulate where we’ve been, who we are, and where we’re going,” said Governor Mike DeWine. “The imagery on our new license plate symbolizes what makes Ohio beautiful, unique, and extraordinary.”

Except somebody blundered. Eagle-eyed Ohioans soon noted the Wright Brothers’ plane appeared to be pushing, rather than pulling, the banner. The Flyer was in fact pointing backwards, to the embarrassment of Ohio’s BMV. The BMV corrected the image — literally reversing course — but not before 35,000 plates had already been printed and the story went viral on national media.

As misadventures go, the Ohio license plate blunder was more comical than tragic, though a bad day at the office for someone. When graphic designers do not pay attention in history class it haunts them eventually.

In fairness, the Wright Flyer looks upside-down, with its tail up front in contrast to modern airplanes, whose tails taper toward the rear. An odd-looking bird, the Flyer’s impact was overlooked by many at the time, too. “Fifty-seven seconds, hey?” said one reporter at the Dayton Daily Journal, on the first flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. “If it had been fifty-seven minutes, it might have been a news item.”

Ironically, the significance of that first powered flight in 1903, and the escalation of technology since, contributed to the historical amnesia of the present. Though Wilbur Wright died at the young age of 45 in 1912, his brother Orville lived until 1948. Biographer David McCullough said, “He lived to see aviation transformed by jet propulsion, the introduction of the rocket, [and] the breaking of the sound barrier in 1947.” Fellow Ohioan Neil Armstrong, brought a swatch of cloth from the wing of the Wright Flyer with him to the moon in 1969, fulfilling an odyssey barely imaginable a generation before.

In the face of dizzying change, when the past yields little resemblance to the present, how to make sense of the dizzying upheavals of the future? How do those of us following the Wright Brothers and Neil Armstrong avoid the conclusion of that other Midwestern pioneer Henry Ford: “History is more or less bunk. It’s tradition. We don’t want tradition. We want to live in the present and the only history that is worth a tinker’s dam is the history we make today.”

We must begin, as always, in the classroom. If nothing else, Ohio’s BMV blunder showcases the need for history education. With all due respect to Henry Ford, progress detached from humanity leads only to a hollowed-out future. The current emphasis on STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) curricula has its place, but only in the context of human purpose and humanistic understanding. A generation that loses sight of where it came from, and where it is headed, can expect nothing good.

In the midst of incredulity and online mirth surrounding the license plate fiasco, let us not lose sight of where we are pointed together.