Myaamia Heritage Award student reflects on experience

The author, seen here at the Myaamia Center in 2020, has studied the Myaamia language.

August 13, 2021

Filled with uncertainty, I opened the creaky door to a small log cabin on the edge of Miami University’s Western Campus where I found a group of friendly, but unfamiliar faces.

On the first Friday of the fall semester, the Myaamia Center, a cultural center for the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma on campus, hosts a mandatory, one-day retreat for its staff and students attending the school via the Heritage Award program.

The Heritage Award Program, according to Miami’s website, is a four-year undergraduate experience for members of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma or Miami Nation of Indiana who meet regular admission requirements at Miami University. The program includes a waiver of instructional fees, educational support from Myaamia Center staff, and requires students to participate in a Heritage Class series, followed by a senior project.

I attended my first retreat as a freshman in 2018.

I had met the other nine freshmen a few days earlier. I gravitated toward the first two people I knew, as everyone else already seemed to know each other.

Eventually, Bobbe Burke, coordinator of Miami Tribe Relations at the time, made her way to our small group.

“How was the first week of classes?” she asked us.

Burke started working with the tribe at Miami University in 1991, taking the role of coordinator in ‘94. She was quickly given the name “Tribe Mom” by the freshmen that year as she checked in with us frequently and became the first person called when we needed help with all things Miami-related.

“Hoci!,” (a Myaamia word meaning “attention please”) yelled George Ironstrack from across the room, the chatter went silent and the retreat officially began. For five long hours, we sat attentively listening to information about the tribe, presentations from our peers, and playing Myaamia games.

Much to my relief, around midnight, the retreat seemed to be winding down, until Ironstrack pulled a small, fake fire from his bag and informed us we would be doing something called a Stomp Dance around it.

I panicked a little. This part definitely wasn’t mentioned at orientation. I reluctantly took a place in the circle and tried my best to do what everyone was doing, but I still felt out of place.

I realized at that moment, I didn’t really know anything about my Myaamia culture, community, or its deeply rooted ties to the university I was attending.

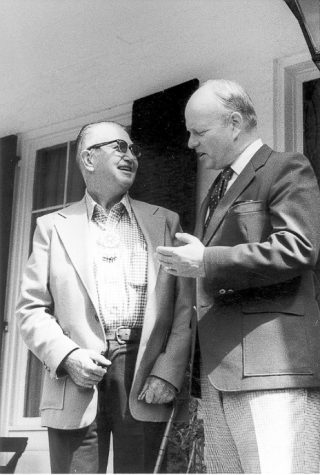

The relationship between Miami University and the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma began nearly 50 years ago when Chief Forrest Olds of the Miami Tribe decided to stop by for an unexpected visit. Before multiple forced removals, the Miami Tribe’s homelands were located in what is now Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, and Wisconsin. Upon this meeting, the two entities recognized their connection through a shared name and land. From this, a relationship began. The relationship, built of trust, commitment, and shared dedication to education, according to Miami’s website, has brought over 100 Myaamia students to Miami University via the Heritage Award Program.

Burke said much of the relationship’s early years were focused on Miami’s mascot. The school started using the term “Redskins,” along with a stereotypical “Indian head” logo to represent their athletic teams around the 1930s. There was controversy at Miami the year before Chief Olds’ visit regarding the insensitivity of the mascot. So, Miami sent a resolution to the Tribe shortly after the visit regarding its use.

At the time, the Tribe wanted to focus more on the relationship than the mascot.

“Chief Olds said the term didn’t belong to the Myaamia people anyway,” Burke said.

The tribe agreed to allow the use of the mascot in a dignified manner, Burke said. But due to a lack of education and understanding on both sides- that never quite worked out.

After Chief Olds died, Chief Floyd Leonard would occasionally visit Miami throughout the 1980s and the Anthropology Department began offering a few study opportunities about the Tribe. Aside from this, not much was happening in the relationship during this time, Burke said. The relationship really started to change in 1991 when Miami brought the first three Myaamia students to campus.

Rachel Eikenberry, one of these first students, attended Miami from 1991-1994 as a graduate student and Heritage Award recipient. Eikenberry said she didn’t know much about her connection to the Tribe at the time but she was still interested in Miami as a school.

“It was kind of like a big leap of faith,” Eikenberry said. “I’m a lifelong learner- I wanted to learn about the School of Psychology and my Tribe and it took me on this crazy ride.”

Eikenberry said she was asked to sit on the President’s Council to examine the use of Miami’s mascot. Chief Leonard, who Eikenberry described as a humble and kind leader, was grateful for the relationship with Miami and worried about offending the school during a delicate time.

“He just trusted me to make the right decision in these meetings,” Eikenberry said. “I was just one of many on the committee, but I was the only tribal member and it wasn’t my decision to make.”

Eikenberry would call other tribal leadership for advice while on this committee until the committee agreed to change the mascot to “Redhawks” in 1992. The transition didn’t begin until 1997 when the Tribe officially requested its change.

“I’m so proud that we came to that conclusion and I got to be a part of it,” Eikenberry said.

After graduating from Miami, Eikenberry returned to Iowa, where she still lives today, to pursue her passion as an educator. Eikenberry continues to deepen her connection to the Miami Tribe community through her remote work on the Miami Nation Enterprises Board.

She said she was moved in 2018, when the Myaamia Heritage Logo, a visual representation of the relationship designed by both the university and the Tribe, was placed on athletes’ uniforms.

Kimberly Wade attended Miami as a Heritage Award student from 1996-1999 as a nursing student. Originally from Miami, Oklahoma, where the tribal headquarters is located, Wade said she felt like an outsider at Miami University.

“I was really homesick,” Wade said. “We didn’t meet up as a group or anything like you all do today.”

While trying to find her place at Miami, she said she was suddenly involved in the mascot controversy- all because of her license plate.

Members of federally-recognized tribes, like the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, don’t have to register their vehicle with the state but instead can register their vehicle with their nation. Wade said that in places like Oklahoma, where Native populations are significantly higher, these license plates don’t stand out. However, in a place like Ohio, they’re quite noticeable.

One day during her first year on campus, Wade was blocked in a service lane while trying to turn her car around. She said she wasn’t sure what was going on until she noticed a man looking at her license plate, realizing she was a tribal member.

“I walked over to his car and he started asking me all these questions about where I lived on campus,” she said. “And I just told him everything he wanted to know.”

When Wade returned to her dorm after the strange interaction, her roommate informed her the Channel 9 news station called looking for her.

“They wanted to know what I thought of the mascot issue,” Wade said. “I just told them that I stood by my tribe’s request and they quoted that in the Cincinnati Enquirer.”

Shortly after the story ran, Wade said people began writing into the Enquirer, calling her a hypocrite for accepting a scholarship from the school while publicly disagreeing with them.

“I felt like I needed to make a good impression for my people,” Wade said. “But it was just this huge responsibility I didn’t realize I would be undertaking.”

In 1997, an entity like the Myaamia Center didn’t exist to handle public matters like this, Wade said. So, the responsibility fell to the students to speak for their community.

Bobbe Burke said the Heritage Program began to shift away from this disconnected space in 2001, when Daryl Baldwin, now director of the Myaamia Center, began his Myaamia language revitalization work at Miami.

Within a year of starting the Myaamia Project, (now the Myaamia Center) Baldwin began creating a three-course series about the Miami Tribe. The classes would eventually become a Heritage Award requirement in the years following. This is when Myaamia students began seeing each other on a weekly basis.

“We finally had close contact with the students,” Burke said. “But they didn’t really know each other or interact with each other- let alone live together like so many of you do now.”

George Ironstrack, assistant director and head of education at the Myaamia Center, came to Miami University as a graduate student studying history, while being able to work with the Myaamia Project to enrich his cultural awareness.

“Miami gave me the opportunity to not only work on my graduate degree but also connect with my Myaamia community in a way that no other place could,” Ironstrack said.

In 2008, Ironstrack, a member of the Miami Tribe, said he was made aware of an education position opening up at the Myaamia Project. Drawn to the position for its community cultural aspects, Ironstrack started as the third employee at the Myaamia Project reorganizing the courses Baldwin had designed.

Ironstrack said his first years teaching the Heritage Courses at Miami were rewarding but also challenging. The early classes only had about 12 students and getting a conversation started was his biggest struggle.

“It was really hard to overcome students’ inhibitions about not knowing anything,” Ironstrack said. “I recognized this burden to learn about your community but also feeling some guilt about not knowing anything.”

Since these early classes, Ironstrack said the Myaamia Center has worked more carefully to identify these anxieties early on, leading to more interaction between students and instructors, in and out of the classroom.

“Now the energy within the Heritage Program is a lot more self-sustaining,” Ironstrack said. “We kind of get it going, helping to acclimate students to campus during their first year, but after that students take a lot of responsibility for keeping it going themselves.”

One of the Heritage Award students who help carry that responsibility today is Josh McCoy, a junior, computer science major at Miami. McCoy and I both came to Miami our freshman year as part of the Heritage Award Program and now live together with other Myaamia students.

McCoy said he started visiting Miami University around age 8 when his father began working with Baldwin on an ecological project. He’s grateful his father started this work as it gave him an opportunity to be exposed to some of the language and culture from a young age.

Since coming to Miami, McCoy said his identity as a Myaamia person has only strengthened. He organizes a Myaamia intramural broomball team every semester, a Myaamia sap collection in the spring, and became president of the Native American Student Association to encourage all students at Miami to learn more about Native cultures.

“I mean just knowing that those maple trees we tap could be some of the same trees our ancestors tapped in the 1700s is really powerful,” McCoy said in reference to his maple sugaring work. “Just being able to develop this identity in the same place as our ancestors is so important to me and I want to share that feeling with my community here.”

What started as a relationship rooted in a misunderstanding between two cultures, brought those cultures together in a fashion that now fosters learning and understanding between the two. To date, the Heritage Award Program has helped over 100 Miami Tribe students like Eikenberry, Wade, McCoy and myself, deepen our own cultural identities in ways we couldn’t imagine.

The Myaamia Project, once a one-man office, is now the Myaamia Center, located in the center of campus, with 15 staff members and a new position being developed for Fall 2021. The Heritage Award Program will also welcome its largest freshman class of 14 students in Fall 2021 for a total of 42 Myaamia students enrolled in the program.

Much like McCoy, my Myaamia identity has only been strengthened since coming to Miami University. When I arrived on this campus in the fall of 2018, I had no idea what it meant to be a Myaamia person. Through the intentional work of people like Baldwin, Burke and Ironstrack, I now find myself spending more time with my Myaamia community than anyone else. Fellow students like McCoy, who are passionate about our shared culture, have also brought me closer to my heritage.

We live together, we speak pieces of the language together in our daily lives and play traditional Myaamia games together. Stomp dances eventually became one of my favorite ways to connect with my broader Myaamia community at our gatherings in Miami, Oklahoma.

I now recognize that sharing our history, our language, and our cultural practices creates a unique bond within this community that cannot be replicated anywhere else.