Miami unveils basketball statue on Wayne Embry Day

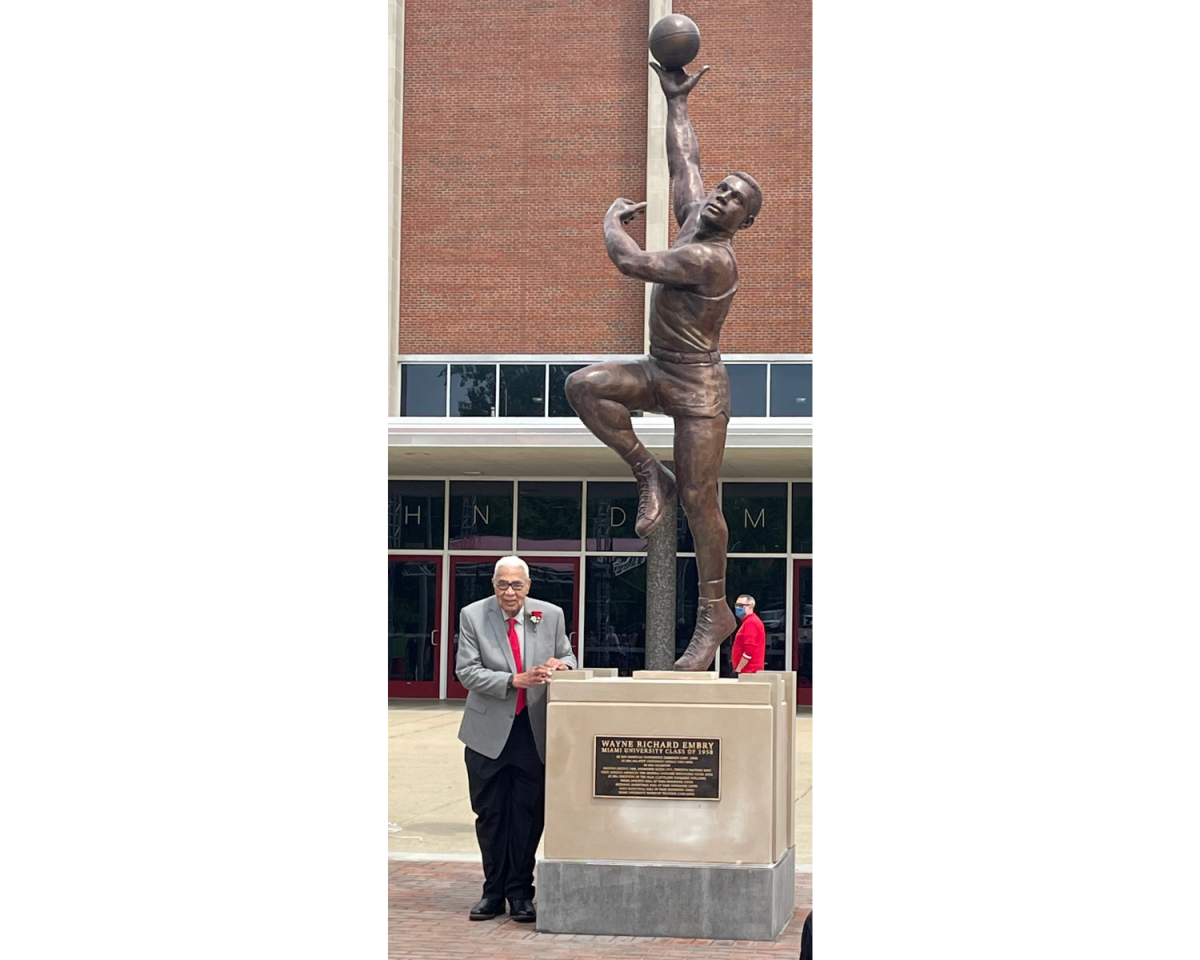

Embry poses beside the statue of himself in front of Millett Hall.

May 20, 2021

During Wayne Embry’s statue unveiling ceremony Tuesday, outside Millett Hall, the Miami basketball legend said he’s made two decisions he considers the most important of his life.

The first was his decision to attend Miami University.

The second was his decision to marry Theresa Jackson Embry, also known as Terri Embry.

Embry met Terri at Miami, where he starred on the basketball court. He was the first RedHawk to reach at least 1,000 career points and rebounds, and eventually, his number 23 jersey was retired by the school.

On Tuesday, Miami went a step further: A statue of Embry, shooting his signature hook shot, was unveiled in front of the south entrance of Millett Hall, the main entrance for fans coming into the arena.

The reveal was the ending of an hour-long ceremony during what the university called Wayne Embry Day. Embry and Terri, who died last August at the age of 82, received three honors: The statue, a basketball scholarship in Embry’s name, and the Freedom of Summer ‘64 Award, which was jointly awarded to both Wayne and Terri.

The Freedom Summer of ‘64 Award is given out annually to a person or entity who advances civil rights and social justice. The first recipient of the award was the late U.S. Representative John Lewis (D-Georgia), in 2018.

Embry takes full credit for his statue, which he earned with hard work and determination on the basketball court. He’s still one of the best players in school history and may be the most successful NBA player to attend college in Oxford, Ohio.

The Freedom Summer of ‘64 Award? Well, that’s a little bit more complicated.

“I’m only accepting about 25% of this award,” Embry said. “The other 75% goes to Terri.”

Embry talked about the activism of his late wife, including her trip to Alabama in 1965. Terri and Yvonne Crittenden, the wife of Embry’s then-teammate, Oscar Robertson, went to Alabama in March to participate in civil rights marches from Selma, Alabama to Montgomery.

Terri was also very active with the National Urban League. Embry recalls coming home from a practice or a road trip and asking her what she had done that day. The answer was always the same.

“‘Well, I was down at the Urban League, we have some things we’re working on,’” Embry said, imitating Terri.

He called her “a great advocate of change,” and a mentor to many young people.

Of course, Embry was an advocate of change himself. He enrolled at Miami University in 1954 and was one of Miami’s first Black student-athletes. After five NBA All-Star appearances, Embry retired and moved to a front-office position with the Milwaukee Bucks.

In 1972, Embry made history by becoming the first African American general manager in the NBA. Then, 20 years later, he won his first NBA Executive of the Year award with the Cleveland Cavaliers.

Embry’s trailblazing career, both on the court and in the front office, is an inspiration for many at the school. DeUnna Hendrix, the women’s basketball head coach for Miami, was the first black woman hired to the position in school history. Hendrix knows that without Embry’s contributions, she might not be in the position she’s in today.

“You know you’ve reached greatness if you can inspire others, and that’s what he’s done,” Hendrix said after the event.

Hendrix was at the ceremony Tuesday, which was open to the general public. Also in attendance were men’s basketball head coach Jack Owens, as well as a few players from the men’s and women’s basketball teams.

Women’s basketball guard Peyton Scott and men’s basketball guard Myja White were both involved in the ceremony. Scott spoke before Embry was awarded the Freedom Summer of ‘64 Award, while White recited a poem he wrote about Embry before the statue was revealed.

Scott says Embry’s legacy shows her the impact athletics can have in advocating for and elevating others. Scott also thanked Terri for her leadership, which she said has inspired her.

“She has set the stage for me to be a confident and unwavering woman in this world, who has a voice to be heard and a presence to be felt as a leader,” Scott said.

To end her speech, Scott called on an old quote from Embry. The NBA legend was once asked if he thought it was significant that he was the first African American general manager in the league.

He responded, “Only if it’s significant to others.”

“The impacts that you and your wife had here at Miami University and far beyond were nothing short of significant,” Scott said.