Miami professor discusses the impact of photographic inventions

Photo taken from her March 17 virtual lecture

Pepper Stetler, assistant professor of art and architecture history, says photography was an invention that changed the world.

March 26, 2021

The invention of photography changed the way we see the world, how we remember things that have happened to us and how we share our views on it, said Pepper Stetler, associate professor of art and architecture history and associate director of the Miami University Humanities Center.

Photography, one of the inventions that changed the world, is one in a series of virtual lectures sponsored by the Humanities Center and the Miami Alumni Center.

Throughout her March 17 talk, Stetler explored how and why various photographic inventions emerged in the 19th century and what the earlier practices share, manipulate, narrate and represent in photographs have in common with our own 21st century obsession of digital images.

“When an object changes the world, how might we understand the world before we were ingrained in the logic and the convenience of its presence?” Stetler said.

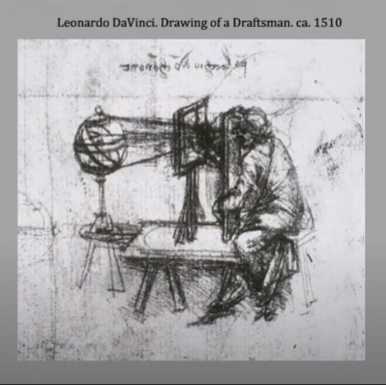

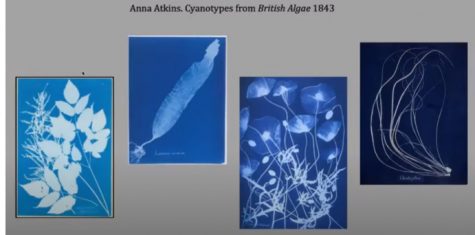

Stetler highlighted five creators who she felt were the most impactful in the invention of photography: Leonardo da Vinci, Joseph Necephore Niepce, Jaques Louis Mande Daguerre, William Henry Fox Talbot and Anna Atkins.

“Photography seems to stand in between the world of art and science,” said Stetler.

Da Vinci (1452-1519) was interested to find a way to record an image without the hand of the artist. In his time, artists did not know the chemistry needed to produce an image. Light sensitive chemicals were not known until about 300 years later.

Niepce (1765-1833) was more interested in creating images of nature and printing them onto a lithographic stone. His major problem was trying to get chemicals in images to stabilize after they had been exposed, causing his images to appear dark around the edges and causing light to appear in different areas on the picture. In Niepce’s photo “View of La Gras 1827,” you can see these characteristics. Niepce considered his work to be a failure.

“He isn’t really interested and doesn’t yet see the value of the photographic image that he actually produced, which to us today might seem pretty amazing,” Stetler said.

Daguerre (1787-1851) had a more artistic experience than Niepce. He was more focused on capturing light to use in his dioramas. In Daguerre’s “Temple of Salomon, 1832,” through various illumination changes, he was able to create a whole new feeling in his picture.

Even today we can see these types of practices and methods in pictures. Daguerre titled these types of images as “The Daguerreotype.”

“If you asked somebody in 1850 what the future of photography was going to look like, they would have said ‘The Daguerreotype,’” Stetler said.

Fox Talbot (1800-1877) had come up with a negative on paper type of photography. In his “Camera Lucida” drawing at Lake Como in 1833, he shows an example of this method. He would press specimens on a surface, exposing them to light and creating an image on paper.

Finally, Anna Atkins (1799-1871) was a botanist who was considered the first person to publish a book illustrated with photographic images. Atkins only used the cameraless photogenic drawing technique to create all of her botanical images. She created albums of cyanotype photogenic drawings of her specimens. Not exactly the crisp and clear images that can produced today with the click of a smartphone.