Back in 1994, the late Wally Edwards, a local resident, was on a mission to protect Oxford’s water quality.

“All the water around here comes from this incredible aquifer,” said Sandy Woy-Hazleton, a board members of the Miami University’s Institute for the Environment & Sustainability (IES).

The aquifer is connected to streams, creeks, and rivers and Edwards wanted to protect water from farm runoff and construction debris, in particular, she said.

Woy-Hazleton said she was overseeing projects that students were doing to satisfy their master’s degrees, with projects such as environmental assessments of the city or university’s carbon footprint. A group of students worked with Edwards to research what they could do to preserve water quality. The best solution they found was to procure easements on the land under which the landowners retained ownership, but agreed that the property would never be developed, even if the property was sold, Woy-Hazleton said.

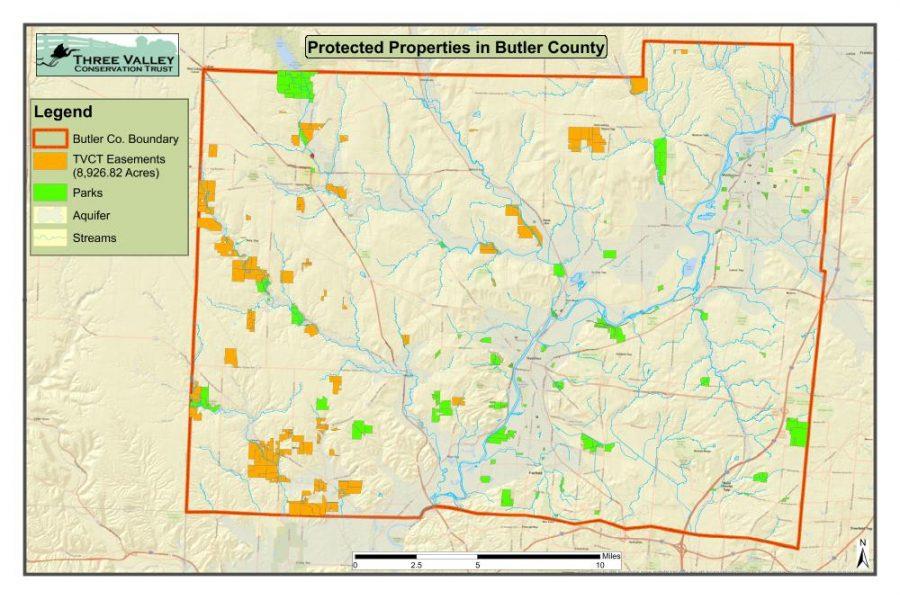

Thus, Four Mile Valley Conservation Trust, was born, named after Four Mile Creek. In those early years, Four Mile was a volunteer organization with a handful of easements. Today, the organization has grown out of just Butler County, and was renamed Three Valley Conservation Trust in 2000 to reflect that change, according to its website.

Three Valley currently has 198 easements that add up to 22,183 acres in total. 87 of those easements are in Butler County, and 91 are in Montgomery and/or Preble Counties. Three Valley has easements in a handful of other counties as well, and has even begun to dabble in Indiana land preservation, with two easements in Union County.

Three Valley deals with two types of easements: those donated to the trust, and those subsidized by the federal or state government.

For donated easements, which make up about half of the easements Three Valley currently oversees, Three Valley works with the owners to draw up a contract. For Three Valley, those easements are almost always kept as natural preserves.

Protect the Land to Keep the Water Clean

“(The contract) reflects the landowner’s wish to not have it developed — to remain in its natural state — either an agricultural area, a wooded area, or environmental area,” said Chad Smith, executive director of Three Valley.

“They say, ‘hey, we would really like to see our whole parcel or farm kept in perpetuity,’ and they’ll typically give a donation at that point,” he said.

For government-subsidized easements, which account for the other half of all easements Three Valley oversees, landowners are paid a percentage of the value they’d get if they sold their property. The percentage landowners are paid varies, Smith said, and the idea is that the money paid to the owners will offset the devaluation the land gets because it is under an easement.

For Three Valley, all government-subsidized easements are farmland, although it is common for a portion of the farms to be natural areas, as well, he said.

Using easements to preserve land began in the U.S. in the 1930s and 1940s, with the National Park Service purchasing easements to protect what it saw as scenic vistas. It paid for easements on 4,500 acres in Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee along the Natchez Trace Parkway, along with 1,500 acres along the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina and Virginia.

Since the mid-1970s, easements have become very popular, and it’s estimated that 40 million acres in the United States—roughly the same size as Florida—are protected under easements.

Because a property owner cannot significantly develop land under easement, it helps to protect the drinking water.

Additionally, in order to prevent farm runoff into streams and creeks, about half of the government-subsidized easements Three Valley oversees have buffer zones between farmed fields and those waterfronts.

Owners plant “native grasses and buffer plants to catch some of that runoff and prevent some of that runoff,” Smith said.

“We try to protect land that has stream corridors running through it,” Smith said. “They’re the drinking water source for all the surrounding communities here… they lead to the Great Miami River and ultimately to the Ohio River.”

Preserve Farmland to Protect Food Supply

At the same time, farmland is being permanently preserved.

“The amount of farmland that’s being lost in the U.S. is incredible,” Woy-Hazleton said. “Our food comes from our farms.”

According to a study from the American Farmland Trust (AFT), an organization dedicated to preserving farmland from development, the U.S. “irreversibly” lost 3.3% of its agricultural land —non-federal cropland, pastureland, rangeland, and woodland associated with farms that is managed to support agricultural production—from 1992 to 2012. The size of that lost land is roughly equivalent to the size of Mississippi.

According to the AFT, losing farmland makes the U.S. more reliant on other countries for food, decreasing American food security.

America’s food security helped make Three Valley’s 25th annual community picnic which was held Sunday, June 9, at Leonard Howell Park on Bonham Road possible.

Picnickers noshed on Italian and turkey clubs, chips, queso, and cookies provided by LaRosa’s, and listened to local artist John Kogge play what he terms an “Americana” blend of music.

“It’s just a way for us to thank our members and also invite people from the community to stop by,” Smith said.

“We just to get members together, have a good time, let them know that their support is definitely worthwhile, answer any questions that they might have, let them know who the board is, who the staff are, etc.,” said Mark Boardman, chair of the board.