As soon as he could walk, the Chicagoan was skating on the ice.

He was born on the ice, molded by challenge and competition en route to his emergence as the embodiment of hockey in human form.

“I was around it [hockey], it was kind of in my blood,” said Anthony Noreen. “It was something I knew I wanted to do.”

As early as grade school, he knew hockey was his destiny.

“My parents found something that I made when I was in second grade,” said Noreen. “It was a ‘What do you want to be when you grow up’ [assignment] and it was a picture of me, I’m guessing it was me, the stick figure standing up, and a bunch of guys with USA hockey jerseys on in front of me.”

Noreen lives and breathes hockey, competing on teams since he was 4-years-old, playing all four years of college at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point; the same college that launched his professional coaching career.

Noreen coached for six programs as assistant and head coach: The University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, Youngstown Phantoms, Orlando Solar Bears, Tri-City Storm, USA U19 and USA U18 national teams before he made Miami University his new home.

Most recently Noreen coached for the Tri-City Storm, over his seven years at the helm, he amassed a record of 236-126-24-18, making him the winningest coach in Storm history.

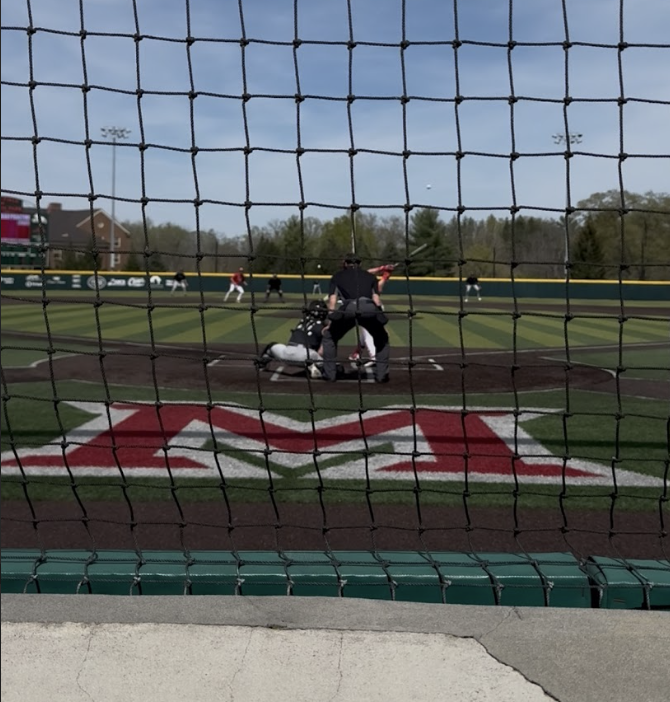

Noreen, 41, became the Miami RedHawks Hockey Head coach in April 2024 and has since strived to reclaim the glory days of Miami Hockey, implementing a fresh culture and instilling crucial principles and values into his players, things that he developed at every stage of his career and life. Noreen grew up as the youngest of three siblings, a brother and sister, in a middle-class household in Chicago. He is a single man, with solely hockey on his mind.

Through his father and older brother, he obtained a ferocious competitive spirit he brings into all aspects of hockey and life.

“My dad was my first coach and coached me from five until I was 15,” said Noreen. “He was on every staff of every team I played on. I don’t think he ever once gave me a compliment. I always could have been better, could have worked harder, could have always shot more pucks, could have lifted more weights, could have ran more… whatever it was to get better at hockey I always could have done more of.”

His older brother taught him to put everything into what he did.

“My older brother didn’t make it easy and I’m very appreciative to him for putting me in the net and shooting pucks at me when I was 6-years-old and, you know, making me lose my fear of ever blocking a shot,” said Noreen.

For Noreen, it was this tough-love model that gave him a drive and push to be the best competitor possible.

“There were a lot of days I didn’t like him [his dad] but he pushed me outside of my comfort zone and made me better,” said Noreen. “I’m forever thankful because it was not what he wanted to do and he didn’t like the fact that I didn’t like him a lot of times but once he passed me on to other coaches he never critiqued me once and he’s been there for advice, he’s been there for help and he’s been an overwhelming support system.”

Sometimes people need to hear things they don’t want to hear to be better. Noreen made it a point to balance encouragement and criticism to develop the players and young men under his tutelage.

“That’s kind of the secret sauce right there,” said Noreen. “Leadership and coaching is not a one-size-fits-all [and] I think there are certain things, your non-negotiables, [where it] doesn’t matter how you feel, this is done [and] there’s the right way [and a] wrong way…The expectation is [to] do this the right way but underneath that I think there’s a …kind of the magic to coaching [and] leadership. Find[ing] a way to get the best out of a player, out of an individual, to push them outside of their comfort zone and maybe help them reach a level that they don’t even know they’re capable of.”

The way Noreen leads his players is among many reasons why several fifth-year players, such as Defenseman Dylan Moulton, returned to play.

“When I met with him, he said all the right things,” said Moulton. “Like, the way he came in with the attitude that he brought, the ambition that he had to want to turn this place around and make it what Miami hockey is supposed to be. It was very obvious from the start and it made my decision to come back here and play for him very easy.”

Noreen constantly talked about maximizing the potential of oneself through rigorous discipline and consistency.

“They [the players] represent their family and the university off the ice, on the ice, win-lose, whatever,” said Noreen. “We need to make sure that we instill a discipline in them and this is probably the key thing to make sure that they keep to that no matter what the circumstances are… the discipline to make sure you are doing what you’re supposed to do at the highest level, when you’re supposed to do it no matter what…it goes back to that discipline word but resilience, to me, [will] get you further in life than just about anything.”

Players like Center Ryan Sullivan noticed how Noreen maintains consistency and helps his players follow suit.

“So far, I’ve really liked how he’s, you know, he’s taken ownership and development for every player he’s carrying and, you know, his messaging doesn’t change,” said Sullivan. “I think, oftentimes, when you win or lose, sometimes it can hit a panic button, but from what I’ve seen, I’ve appreciated the consistent messaging and attitude.”

Noreen demanded high expectations from his players when he began coaching and continues to do so for his RedHawks squad, according to fifth-year defenseman Hampus Rydqvist.

“He’s like one of the guys that you can talk to in a friendly way too, but at the same time, the conversation is a high ceiling on the conversation,” said Rydqvist. “He expects a lot from you, and you expect a lot from him, and it’s a good way.”

More than anything, Noreen reiterated how he loves doing what he does and who he does it for.

“We get to be around young hockey players and influence their lives,“ said Noreen. “We don’t take that lightly. We have 30 guys sitting in there depending on us. We need to put as much time into them as possible. We have a university, we have an alumni group, we have people that love this place, believe in this place, that, you know, want to see us get it back on track and like, we owe it to them to put everything into it. I just don’t know what else I’d rather be doing.”