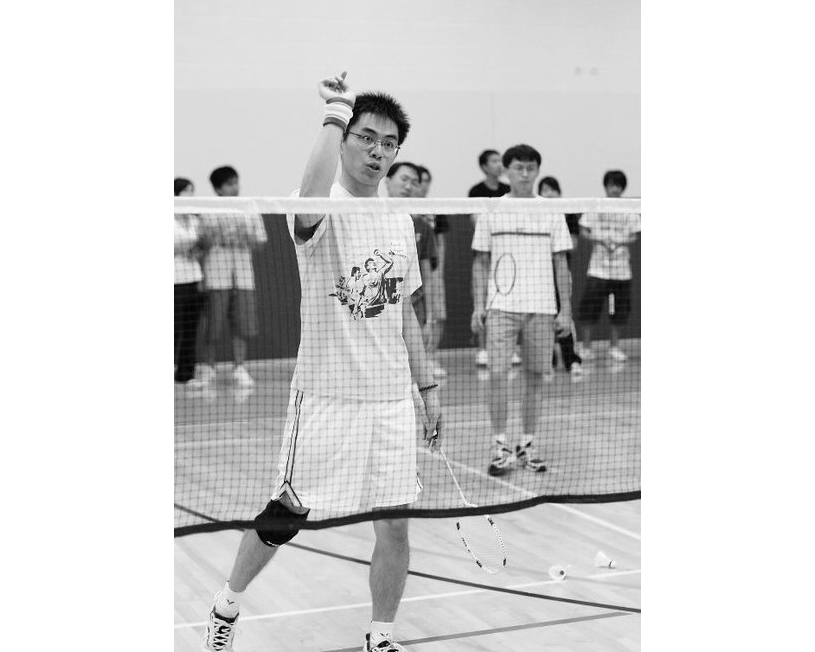

Hitting the birdie back over the net to his client, Po-Chang Chen was all business — at least with badminton.

“It’s a pretty fair game,” said Chen. “There’s no business involved whatsoever… It’s unlike, you know, like golfing.”

But that was back in Taiwan, where Chen worked as a business analyst for a regional consulting firm, ABeam Consulting. Now, Chen is the faculty advisor for Miami’s badminton club, in addition to his role as an associate professor of accounting for Farmer School of Business.

While working for ABeam Consulting, Chen began to consider what his life and work would look like in the long term. He knew many of his professors at National Taiwan University had studied at U.S. institutions to receive doctoral degrees, so Chen thought he would give it a shot.

“At that time,” said Chen, “what I told myself is that I will do the applications for this one time. If it works, then great, I will go. If it doesn’t, no big deal. I’ll stay where I was.”

Chen’s immigration story is just one of many that illustrate the changing tides of U.S. immigration policy. This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Immigration Act of 1924, considered to be one of the U.S.’s most restrictive immigration laws.

According to Matthew Smith, visiting assistant professor of history at Miami’s Hamilton campus, the Immigration Act centered on ethnic origin. The explicit goal of the Immigration Act was to “preserve the ethnic heritage of the composition of the United States as being northern and western European,” said Smith. “[It] also effectively outlawed immigration from China and other Asian countries.”

The Immigration Act would not be repealed until 1965 under President Lyndon Johnson’s administration with the signing of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Less than 50 years later, Chen would arrive at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign to pursue a doctoral degree in accounting. But had it not been for a prior influential stay in New York City, Chen might not have applied to any U.S. doctoral programs at all.

As a college sophomore, the Taipei City native spent four weeks learning English at Columbia University through a program coordinated by a Taiwanese institution. Chen experienced the whirlwind of New York City, going to musicals on Broadway, riding the subway after midnight and even getting the camera his parents had gifted to him for the trip stolen on the very first day.

“Overall,” he said, “it was a super fun experience. Definitely a lot of fun memories.”

Out shopping one day in New York City with three friends from class, Chen was looking at a pair of Skechers in a shoe store and inquired about the price to an employee. They were expensive, and Chen said he wouldn’t purchase them. But the shoes Chen had on were worth more than the Skechers. “So he [the employee] did not believe that I couldn’t afford that pair of shoes,” recalled Chen. “He said, ‘Look at the shoes you’re wearing.’”

“And [then] he said, ‘Go back to China.’”

Shocked, Chen and his friends left the store.

Rather than let this experience sour his perception of New York City and tarnish any feelings he possessed to later come back to the U.S., Chen metaphorically took off his expensive shoes and stepped into the employee’s instead.

“Maybe that person had a bad day,” Chen hypothesized, “and hadn’t sold any pair[s] of shoes.” And looking at … the four Asian people here, … maybe based on their experience, people from Asia, like from China, they come here and they shop a lot. But then we were just there, we didn’t want to buy anything. So maybe that’s what caused the person to say something like that.”

When Chen got back to Taiwan, he immediately signed up for his school’s English program. His friends did too, according to Chen. “Definitely there’s a correlation between that trip and what we decided to pursue later in our lives,” said Chen.

Of Chen’s three friends, one became a Taiwanese diplomat and the remaining two eventually traveled back to the U.S. to earn doctoral degrees.

“We could turn it on its head,” said Smith, “and say there’s actually an indication of the success of the United States in the fact that people from all over the world, to this day, are coming to the United States.” If immigration were to no longer be a hot button issue, according to Smith, “it will be because people no longer want to come to the United States.”

In 2006, Chen came back. While attending Urbana-Champaign, he rented an unfurnished apartment and had no car. He never lived alone in his life. Away from home, unfamiliar with the area, and venturing into new territory independently, this might have been a problem for some 28-year-olds. But not Chen.

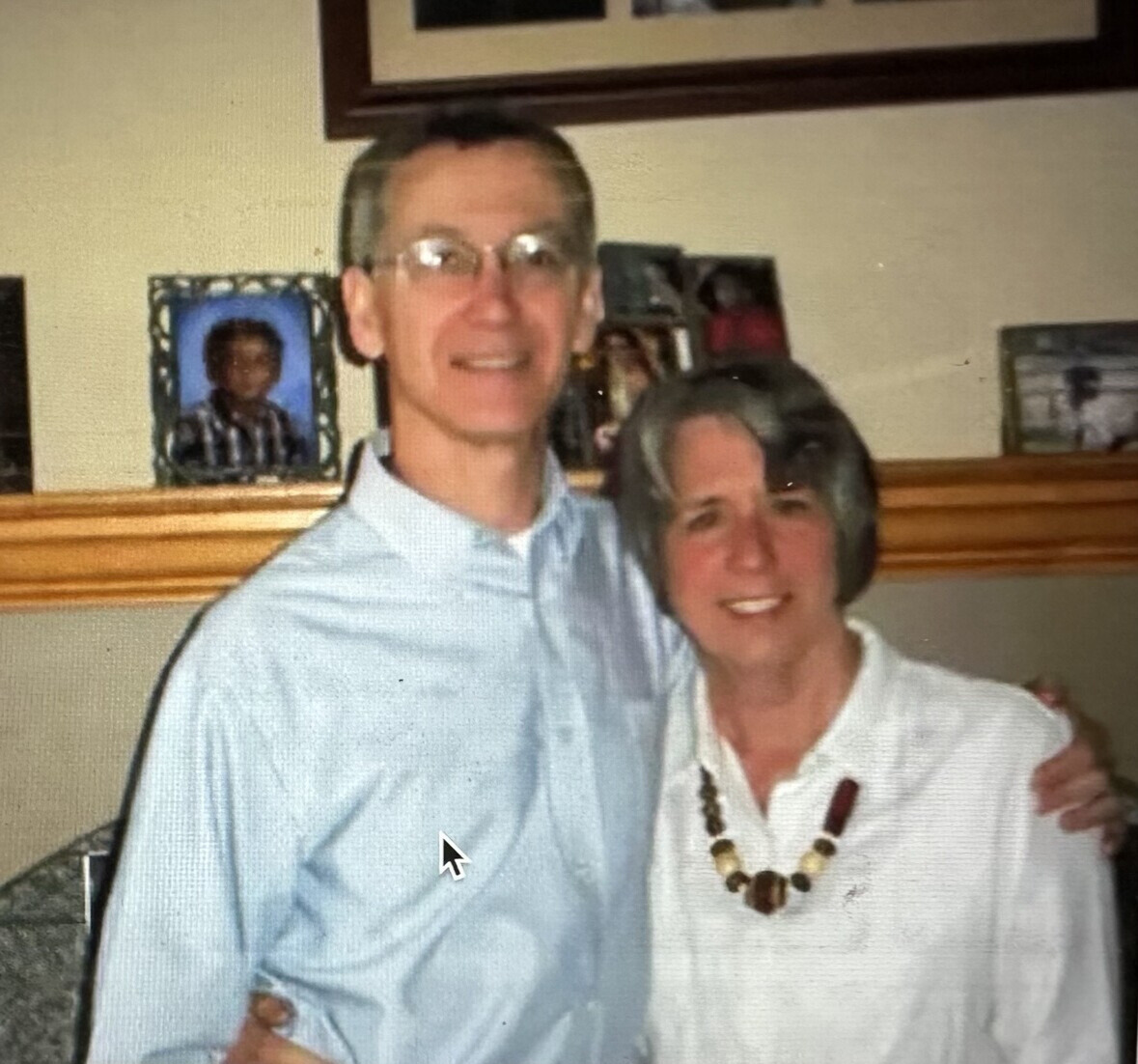

According to Chen’s fellow colleague Jonathan Grenier, a professor of accountancy for Farmer School of Business, Chen is “one of the most positive people I’ve ever met.”

“He acclimated to the U.S. very easily,” said Grenier, who was also in the same doctoral program as Chen. “[He] is also very social in general.”

“Looking back,” Chen reflected, “those [were] great opportunities for me. … I had to put myself out there, interacting with people, and I felt like I enjoyed that a lot.”

So when it came time for a welcome event for the international students of Urbana-Champaign, Chen put himself out there. In attendance with the school’s badminton club, he met another Taiwanese student: Yenlin Chien, his future wife.

Now living in Oxford, Chen said he enjoys Midwestern America.

“I feel like this is where I get to experience a culture,” said Chen, “that shares some commonalities in terms of values, … but also other parts of the American life that I did not get to experience like in Taipei [City].”