Doctoral student puts a unique spin on sustainability

McQuigg spinning yarn on her wheel. A largely self-taught “fiber artist,” she says she works “sheep to sweater.” Photo by Lexi Scherzinger

February 14, 2020

Her set-up is quaint. The basement is small, but with high ceilings and a whole wall of shelving stocked full of bags of wool and fiber. Two different colors of carpet loosely cover the unfinished cement floor. A green lawn chair sits in front of a small spinning wheel, with a basket of raw wool fiber close by.

Jess McQuigg calls herself a fiber artist.

She taught herself to knit more than a decade ago using library books and YouTube videos. In 2015, she bought her first drop spindle, a small, hand-held spinning device. Now, she spins every day.

Last year alone, McQuigg made three and a half sweaters, with the final half-sweater still sitting on a loom downstairs. She calls the process “sheep to sweater;” buying raw wool from a local shepherd, then doing all other steps herself to make a garment, including scouring, carding, spinning and weaving. It takes up to a year to finish one sweater, but last year she was ambitious.

She doesn’t sell anything she makes. “To create a business out of it would take that fun sensation away,” McQuigg said. However, half a dozen or so faculty members in her department can be seen wearing her scarves.

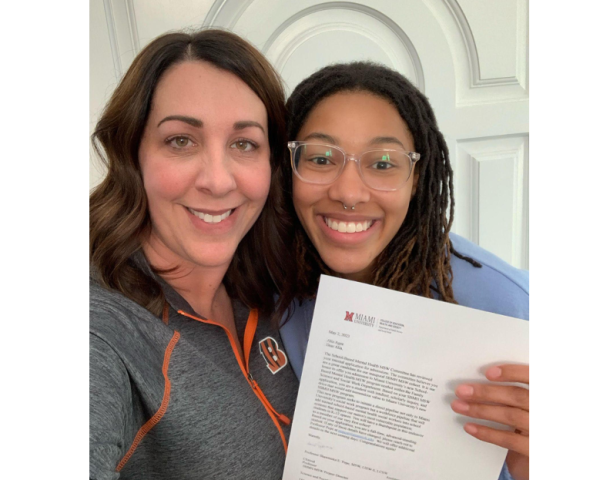

McQuigg is a biology doctoral student at Miami studying amphibian conservation and disease in the midwest. She moved to Oxford for the program in 2015 after graduating from the College of Wooster in 2013. Now, she teaches undergraduate classes on ornithology and environmental ecology and mentions fiber in pretty much every class.

“I’m always talking about fiber in some way,” she said. “There’s so much biology and agriculture and a lot of other aspects that can be incorporated into your average STEM classroom.”

McQuigg’s studies in conservation are intertwined with her spinning hobby. She’s passionate about sustainable living and using as many natural products as possible to reduce her waste stream. She and her fiancé Nick eat almost 100% locally grown food; they grow their own vegetables and get meat from local farmers. Her one-acre plot, just south of Oxford, has room for a large vegetable garden and a chicken coop, home to five hens named Reba, Roxanne, Rene, Radagast and Raven. Radagast is a character from Lord of the Rings, one of McQuigg’s favorite book series.

McQuigg said she and the hen have a love/hate relationship.

The chickens are nice most of the time, but they do love to dig up the garden. “Nothing is safe in the bean plot,” McQuigg joked. Since the hens are free-range, they frequently get up to mischief like sneaking onto the roof or laying eggs in the driveway.

Nevertheless, the ability to harvest four to five eggs daily from her own backyard plays a key role in McQuigg’s homestead goal. Her biology supervisor, Michelle Boone, receives a dozen eggs a week from the coop.

Her Ph.D. program should finish next year. She’s not sure if she wants to stay in Oxford.

Her goal is to teach at a smaller university, and the plot of land she has here is small. She hopes the next house has room for a goat, a few sheep and an alpaca.

Another goal: trying out as many different breeds of sheep’s wool as possible to feel the difference between the fibers.

“Just about every fiber you can imagine has a function,” McQuigg said. “It’s about working with them to figure out what that function is.” From wools to plant fibers to plastic fibers like acrylic, McQuigg is on a mission to try everything.

She’s trying to get away from using plastic clothing fibers, like acrylic, by using plant fibers and wool instead. Plant fibers like hemp are common add-ins to scarves and other projects because they’re shinier and stronger than wool.

A misconception McQuigg said she often faces is that wool is a bad fiber to use, environmentally and morally. She disagrees; sheep from the smaller ranches she supports are treated “incredibly well,” and being shorn is necessary for the health of sheep. In addition, supporting “conservation breeds” helps keep more types of sheep alive.

“There are breeds of sheep with only a few hundred left. The conservation breeding goal is to conserve the biodiversity of sheep breeding,” McQuigg said. “There’s a number of us that strive to use as many of those conservation sheep as possible to keep them in the fiber world.”

Those special types of wool typically can’t be found locally. McQuigg sources them from a shepherd in Oregon. Other than that, the majority of her wool comes from Oxford or Dayton. Her favorite breed at the moment is the Jacob sheep, and she gets that wool from an Oxford shepherd.

So what happens to the dozens of winter accessories McQuigg makes every year? One woman can only wear so many scarves at once. The rest go to Warm Up America, a charity that gives hand-knit and crocheted goods to those who need them, like homeless and elderly people. So far, she and the rest of the biology department have knit more than 80 blankets and 75 hats for the charity.

With charity, waste reduction and decreased pollution, natural hobbies and crafts McQuigg builds sustainability at small and large levels. “You’ve got this global level where you no longer have the plastic pollution or the oil pollution, but you’re also helping local farmers that are trying to make ends meet with a flock of sheep,” she said. “There are community-level benefits to these practices as well as larger environmental impacts.”

But she doesn’t do it just for that. Homesteading and spinning are her passions. “A lot of people don’t realize people still spin, or that it’s really quite simple to knit your own clothing if you build the skills.”

She sits back down on the green lawn chair and picks up a strand of fiber, alternating pedals as the wool spins to yarn. As she gets into the rhythm, she smiles. This is what it’s about for her.